By Alan Whitehorn

The two key human rights concepts of “crimes against humanity” and “genocide” have their roots in the response to the Young Turk mass deportations and massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Following the April 24, 1915 mass arrests of hundreds of Armenian political, religious and community leaders of Constantinople and their subsequent exile and deaths and the massacres of multitudes of other Armenian civilians, the Entente allied powers of England, France and Russia warned on May 24, 1915 that the Young Turk dictatorship would be held accountable for the massacres and the “new crimes of Turkey against humanity and civilization”.

In 1921 Soghomon Tehlirian was put on trial in Germany for having assassinated Mehmet Talaat, one of the key Young Turk triumvirate responsible for the deportations and massacres of Armenians. Raphael Lemkin, a young Polish university student, who would later become a lawyer, wondered why there existed domestic laws to deal with the murder of one person, but no international law to punish those responsible for the mass killing of a million or more persons. During the 1930s, Lemkin suggested the twin concepts of “vandalism” and “barbarism” to deal with such crimes. The former dealt with the destruction of cultural artifacts, while the latter related to acts of violence against defenseless groups. By 1944, these twin concepts had merged into his proposed new international term: “genocide”. The new concept, along with “crimes against humanity”, would become a key pillar of international law.

With the introduction of the two crucial legal concepts of “crimes against humanity” and “genocide”, it remained for scholars and prosecutors alike to apply these principles to specific cases. Over time, increasingly there emerged the need to compare different historical and contemporary examples. Pioneering analytical and comparative books such as Irving Horowitz’s Genocide (New Brunswick, Transaction Books, 1976) and Leo Kuper’s Genocide (Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1981) were penned in this regard. Before long, the field of genocide studies emerged and was formalized with the birth of the International Association of Genocide Studies in 1994. However, a challenge familiar to many in comparative politics arose. Given that most individuals and scholars lack the global expertise to know sufficient detail about all of the major case studies, there was an urgent need for encyclopedias and dictionaries on genocide.

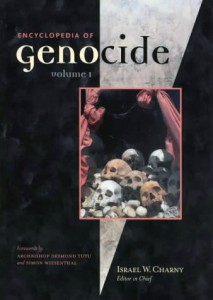

Soon after the appearance of the English language two volume Encyclopedia of Genocide, a French language one-volume version appeared: Israel Charny, ed., Le Livre noir de l’humanite: Encyclopedie mondiale des genocides (Toulouse, Editions Privat, 2001). For the most part, the entries on the Armenian Genocide and other genocides were the same, but there were a few additions and deletions in the French edition. Overall, students of the Armenian Genocide were exceptionally well-served by the two editions.

The one-volume account edited by Leslie Horvitz and Christopher Catherwood, Encyclopedia of War Crimes and Genocide, (New York, Facts on File, 2006) contained only one main entry on the Armenian Genocide and one partial reference in the entry on “crimes against humanity”. This was inadequate coverage of one of the major genocides of the 20th century. It seemed that the pattern had become one of declining coverage. That was about to change.

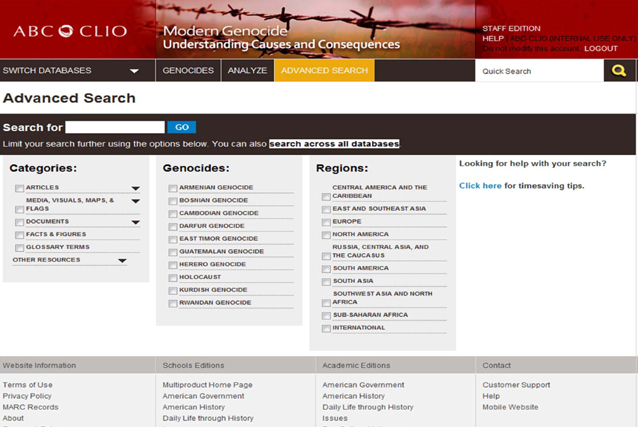

In an Internet age, it was inevitable that an on-line encyclopedia of genocide would eventually emerge. The American educational publisher ABC-CLIO recently created a large database on genocide that was primarily intended for high school students and teachers, but would also be valuable to university students and professors. Entitled “Modern Genocide: Understanding Causes and Consequences”, it is available for an annual subscription fee. Developed in consultation with an advisory board of Paul Bartrop, Steven Jacobs and Suzanne Ransleben, the database continues to grow and be updated. At the current time, it contains seven main entries on the Armenian Genocide (Overview, Causes, Consequences, Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders, International Reaction) by Alan Whitehorn. There are also several discussion essays by various authors (including Colin Tatz and Henry Theriault) on Armenian Genocide recognition and how well the genocide has been known, and about 70 individual subject entries. Entries include pieces done by Rouben Adalian, Paul Bartrop, Zaven Khatchaturian, Robert Melson, Khatchig Mouradian, Rubina Peroomian, George Shirinian, Roger Smith, and others. However, not as many Armenian Genocide specialists have contributed as one might have expected. In addition to the encyclopedia entries and genocide timeline, there are some primary source documents and photos. The online database provides useful insight on the Armenian Genocide. It also suggests what might be possible if all of the entries were to be gathered together into a separate encyclopedic volume that is focused on the Armenian Genocide. Unfortunately, this is something that to date has not yet been done, but which one hopes will occur before 2015.

Quite significantly, all of the genocide encyclopedias together show that the Armenian Genocide constitutes an important case study that is included in each and every genocide encyclopedia from the first to the most recent. This reflects academic consensus amongst genocide scholars that the mass deportations and killings of Armenians constitute genocide. These important scholarly reference works thus provide significant academic documentation that can serve to repudiate the Turkish state’s repeated polemical denials of the Armenian Genocide. Accordingly, these genocide encyclopedias ought to be cited by scholars, jurists and citizens alike. The European Court of Human Rights, in its recent (December 17, 2013) flawed decision on Armenian Genocide denial, should have been aware of such key academic reference works. If they had, their reasoning, in all likelihood, would have been different. Without a doubt, these encyclopedias’ coverage of the Armenian Genocide remind us that time is long overdue for the Turkish government and its citizens to face the dark pages of their history.