By Alexander-Michael Hadjilyra

(Researcher-scholar)

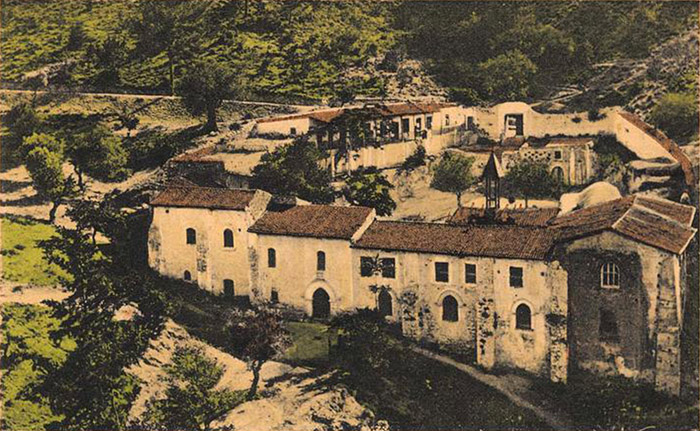

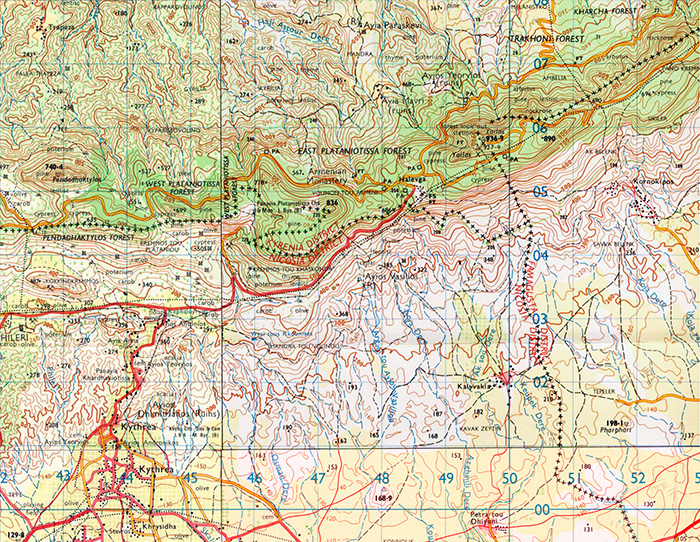

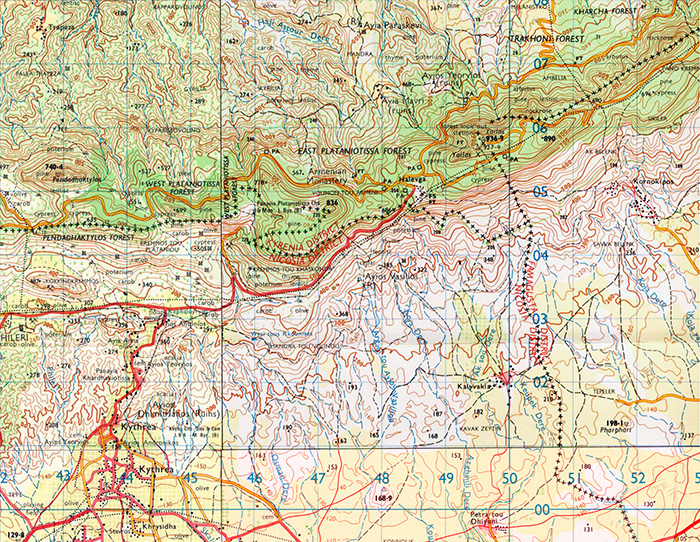

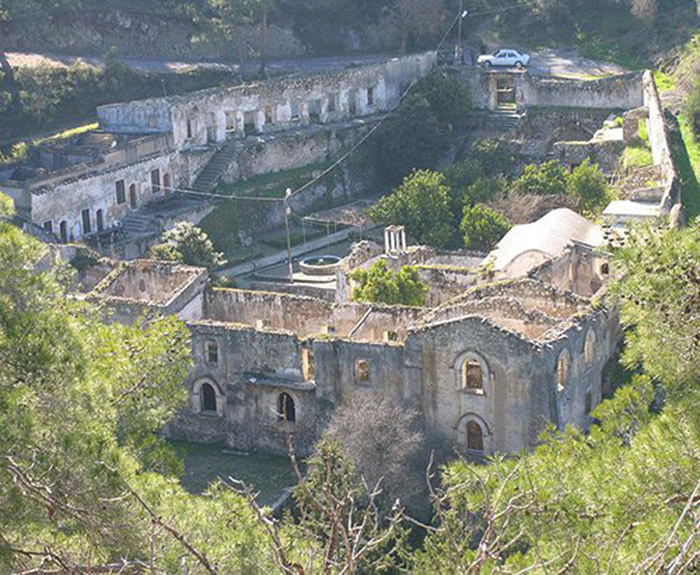

The Sourp Magar (Saint Macarius) monastery, also known as Armenian Monastery or Magaravank, holds a particular sentimental value for the Armenian-Cypriot community. It is situated in a picturesque location within East Plataniotissa forest, about 1½ km to the west of Turkish-occupied Halevga, at an altitude of 530 m. Its vast lands (in total, 8.329 donums or 1.114 ha) extend up to the seashore and include about 30.000 olive and carob trees, whose exploitation constituted the main source of income for the Armenian Prelature of Cyprus until the 1974 Turkish invasion. From the idyllic site of the monastery, one can gaze the Taurus mountain range in Cilicia, especially during the winter, when humidity is low and the peaks are covered in snow.

The monastery was originally established by the Copts circa the year 1000 AD in memory of Saint Makarios the Hermit of Alexandria (306-395), who – according to tradition – had spent some time in the caves of the region as an ascetic. His memory was celebrated the first Sunday of May, although the monastery equally celebrated the memory of Saint Makarios the Elder of Egypt (300-391) in December. Saint Macarius icon, before the chapel entrance, was considered to be miraculous, and the residents of the area believed they could hear the Saint galloping with his horse at night!

By 1425, the monastery had come to the possession of the Armenian Church. Throughout the Frankish and the Venetian Eras (1192-1489-1570), its monks were known for the very strict rules of ascetic life and religious penitence they followed, whereas no females (human or animal) were allowed near the monastery; it is reported that, during the Great Lent, the monks avoided eating pulses that could potentially contain insects, such as beans and lentils. During the Ottoman Era (1571-1878), it was known as the Blue Monastery (Gabouyd Vank, Gök Manastýr), because of the light blue colour of its doors and window blinds.

For centuries, it had been a popular pilgrimage site for Armenian and non-Armenian faithful alike, as well as a way station for travellers and pilgrims en route to the Holy Land, such as Dr. Hovsep Shishmanian (“Dzerents”): inspired by the visible outline of the Taurus mountain range, he wrote in 1875 the historical novel “Toros Levoni”, set in the times of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. According to legend, in 1140 prince of Cilicia Thoros II took refuge here to escape from his prosecutors, as did King Hugh IV in 1348 to escape the Black Death epidemic.

The Magaravank served for centuries as a place of retreat and recuperation for Armenian clergymen from Cilicia and Jerusalem, with which it maintained close relations. Perhaps the most renowned of these was Abbot Mekhitar of Sebaste (1676-1749), who was nursed by the monks until he was healed from malaria in the summer of 1695.

Educator Vahan Kurkjian (Pagouran) deeply admired Abbot Mekhitar work: in 1901, together with the students of the National Educational Orphanage, he erected a stone monument to honour his visit and the 200th anniversary of the Mekhitarist Order on a hill overlooking the south-east of the monastery, which was henceforth called Mekhitaraplour (Mekhitar Hill). In 1931, four former students (Movses Soultanian, Simon Vanian, Armen Bedevian, Raphael Philibbossian) and architect Garo Balian replaced it with a mortar obelisk, which was officially unveiled on 2 August 1931 by Catholicos Sahag II Khabayan and Archbishop Bedros Saradjian.

The monastery won the favour of the Ottomans: following a request by Archimandrite Mesrob in 1642, a firman exempted it from taxation, whose terms were renewed in 1660 and 1701. The period 1650-1750 is considered its “Golden Century”, as huge plots of land were either purchased or given to it. After securing special permits, Archimandrite Haroutiun carried out a large-scale renovation between 1734-1735, while between 1811-1818 Symeon Agha of Crimea financed a complete restoration, during which the new chapel was built to the north of the older one and was inaugurated on 3 January 1814.

It appears that the last monks permanently resided here before 1800. In 1850 it became an annexe of the church of the Virgin Mary in Nicosia. A small-scale renovation was carried out in 1866, by commission of the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, Boghos Taktakian, who – unsuccessfully – attempted to revive the monastic community. Similar attempts were made in 1837 and 1947 by Catholicoi Mikael and Karekin I, respectively.

Since the Ottoman Era and until the mid-1920s, the vicinity was inhabited by Armenian families, to whom some refugees of the Hamidian massacres (1894-1896) and the Adana massacre (1909) were added, who settled in the Adalia (Attalou) and Ais Yiorkis settlements. Pagouran National Educational Orphanage (1897-1904) had its summer sessions at the monastery, where a small school for the Armenian children of the region used to run until 1914.

In 1909 the heirs of Artin Agha Moughalian constructed two rooms. An unknown aspect of history is that, between 1921-1922, the President of the AGBU, Boghos Noubar Pasha, with the consent of Catholicos Sahag II and Archbishop Bedros Saradjian, was examining the housing of an orphanage at the Magaravank.

In 1926 the chapel and the belfry were renovated, by commission of Dickran Ouzounian, Ashod Arslanian and Garo Balian, whereas – by commission of the great benefactor Agha Garabed Melkonian – a paved road linking the monastery with Kythrea was constructed, thus allowing easier access to it. In 1929 the consistory of the monastery was renovated and an iron gate was placed, by commission of Boghos and Anna Magarian.

The square to the east of the monastery was constructed by commission of Catholicos Sahag II, who inaugurated it and unveiled a commemorative stone column on 8 September 1933. Between 1947-1949 the last grand restoration was carried out, by initiative and partial funding of Hovhannes and Mary Chakarian, under the supervision of Vahram Tountayian (Toundjian). By initiative of the Ethnarchy, the Antiquities Department carried out some repairs in 1973.

A major problem was the lack of water. After multiple failed attempts, in 1948 Kapriel Kasbarian drilled a successful artesian borehole (about 300-400 m. south-west of the monastery) and together with his wife, Arshalouis, they donated funds for the erection of the “Archangels” fountain, which was blessed by Bishop Ghevont Chebeyan on 2 May 1948. In 1949, by donation of Sarkis and Sourpig Marashlian, the water distribution network, the turbine and the electricity generator were installed, as witnessed by the only surviving inscription at the monastic compound. In the monastery courtyard there was a circular pool, while the pomegranate trees, the medlar trees, the citrus trees, the hibiscuses and the vines provided a tranquil ambience to visitors.

In 1948 the colonial government granted kotchans (title deeds) to the Prelature for 85 plots of land covering 9.912 donums (1.326 ha): more specifically, 8.902 donums (1.191 ha) in Kharcha, 121 donums (16 ha) in Ayios Amvrosios and 889 donums (119 ha) at the Syrkania quarter of Kythrea – of which 44 donums were eventually appropriated in 1952 (Announcement 532/26-11-1952, published on 3 December 1952) by Kythrea Municipality for the resort in Kephalovrysos to be built.

Between 1957-1961, the Ethnarchy auctioned 845 donums in Kythrea (Kephalovrysos vicinity), whereas between 1961-1963 they sold 574 donums (77 ha) in Kharcha and 120 donums (16 ha) in Ayios Amvrosios (localities: Plaka, Makriyialos, Trakhonas ton Dhaphnon), thus reducing the coastline belonging to the monastery from 1 km to 40 m.

Within the verdant estate of the monastery, with thousands of pine trees and cypresses, there were some mediaeval chapels or their ruins (Ayios Yeoryios tis Attalou, Ayia Mavri, Ayia Paraskevi and Prophitis Elias), many fields, numerous springs, as well as a few watermills.

On 12 June 1966, Archbishop Makarios III visited the monastery, planted an araucaria tree in its yard and gave a £3,000 cheque to Senior Archimandrite Yervant Apelian. As many Armenian children were baptised there, in June 1968 Karnig Kouyoumdjian constructed the chapel new baptistery, in memory of his deceased; by an irony of fate, his granddaughter, Shogher, was the last one baptised there on 14 July 1974.

The estate was also used as a summer resort and a camping site by Armenian scouts and students of the Melkonian Educational Institute, the Melikian-Ouzounian School and AYMA, many of whom had been were Genocide orphans. In 1917 and 1918, the monastery was visited by volunteers of the Armenian Legion, which was formed and trained at Monarga village in the Carpass. The Armenian Women Association also used to host here a few needy Armenian-Cypriot students for some summers.

On the first weekend of May harissa (chicken porridge) was prepared for Saint Makarios feast and the monastery was visited by a large number of Armenian-Cypriots, who used to rent rooms there or at the nearby Goudsouzian, Ouzounian-Soultanian and Philibbossian-Nishanian houses during the weekends and the holidays. Up until the 1950s, the Church also had an inn (1922), which was later on abandoned.

For centuries, the monastery had been an important spiritual centre. Until the early 20th century, a large number of exquisite and priceless manuscripts written at the monastery scriptorium between 1202-1740, numerous ecclesiastical vessels and vestments were kept here, which were moved to Nicosia for safe-keeping. In 1947, 65 illuminated manuscripts were re-located to the Catholicosate of Cilicia in Antelias and as of 1998 they are kept at the “Cilicia” Museum of the Catholicosate. The ecclesiastical had an adventure of their own, as in 1964 – amidst of the inter-communal troubles – were taken with many difficulties to the government-controlled sector of Nicosia. However, the altar and the icons of the chapel were stolen in 1983.

Unfortunately, the Magaravank was occupied by the Turks on 14 August 1974. The last field guard, 75-year-old Garabed Toukhtarian, chose to remain enclaved at the monastery, where he passed away in March 1975. Afterwards, the occupying regime used the monastery to house initially illegal settlers from Anatolia and later on Turkish officer families. The compound was partially damaged by a fire in June 1995. Between 1998-1999 and again in 2005, the occupying regime intended to turn it into a 50-bed hotel with a casino; thanks to organised reactions, this unholy plan was averted.

In April 2006 the Armenian-Cypriot community leadership was able to visit the abandoned monastery for the first time since 1974. Thanks to the initiative of Representative Mr Vartkes Mahdessian and the Ethnarchy, under the supervision of UNFICYP, the annual pilgrimage was revived on 6 May 2007, with the participation of about 250 people to the derelict monastery, including some who had come especially from abroad; the pilgrimage was repeated on 10 May 2009, 9 May 2010, 8 May 2011, 13 May 2012, 19 May 2013, 18 May 2014, 10 May 2015 and 8 May 2016, with the participation of a large number of pilgrims. On 17 May 2016 it was listed as a Schedule B ancient monument (ΚΔΠ 189/2016).

Left at the mercy of natures and vandals, the Magaravank today is ruined, derelict and desecrated. Between 2018-2019 the Technical Committee for Cultural Heritage carried out a feasibility study for the monastic complex and its partial restoration, which started in 2020, however – because of the situation with the coronavirus – progress has been slow.