YEREVAN (Armradio) — The South Caucasus, situated between the Black and Caspian Seas, geographically links Europe with the Near East and has served as a crossroad for human migrations for many millennia. However, ancient mitochondrial DNA evidence finds no upheaval over the last 8,000 years.

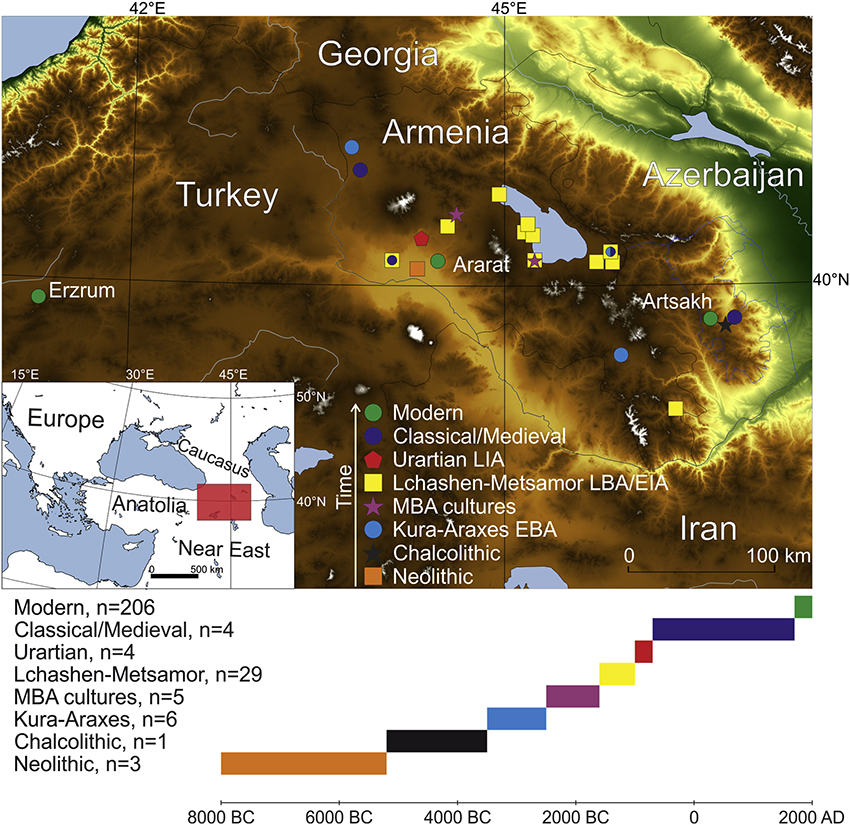

A new study published in the Current Biology sheds light on maternal genetic history of the South Caucasus region. Scholars have analyzed the complete mitochondrial genomes of 52 ancient skeletons from present-day Armenia and Artsakh spanning 7,800 years and combined this dataset with 206 mitochondrial genomes of modern Armenians.

Researchers have also included previously published data of seven neighboring populations. Coalescence-based analyses suggest that the population size in this region rapidly increased after the Last Glacial Maximum ca. 18 kya. The lowest genetic distance in this dataset is between modern Armenians and the ancient individuals, as also reflected in both network analyses and discriminant analysis of principal components.

In the study scholars present 206 mitochondrial genome sequences from three sub-populations of modern Armenians and 44 mtDNA genomes from ancient individuals excavated in Armenia and Artsakh. The calibrated radiocarbon dates of the ancient samples ranged between 300 and 7,811 years BP, with the majority being Bronze Age individuals, 3,000 to 4,000 years old.

Using genetic data of modern Armenians, researchers suggest that the Armenian gene pool was formed as a result of admixture events happening ca. 4,500 years BP. “Our ancient DNA (aDNA) data suggest that at least the maternal gene pool in the South Caucasus has been very stable and was largely formed before these events. A scenario of genetic continuity is supported by two previous studies that included low-coverage genomic data from a few ancient individuals from the South Caucasus: Allentoft et al. observed genetic similarities between Bronze Age individuals (ca. 3,500 years BP) and modern Armenians [26], and Lazaridis et al. showed similarity between Chalcolithic (ca. 6,000 years BP) and Bronze Age (ca. 3,500 years BP) individuals excavated in Armenia [7],” scholars say.

The results have implications for how the known cultural shifts in the South Caucasus are interpreted. It appears that during the last eight millennia, there were no major genetic turnovers in the female gene pool in the South Caucasus, despite multiple well-documented cultural changes in the region. This is in contrast to the dramatic shifts of mtDNA lineages occurring in Central Europe during the same time period, which suggests either a different mode of cultural change in the two regions or that the genetic turnovers simply occurred later in Europe compared to the South Caucasus. More data from earlier Mesolithic cultures in the South Caucasus are needed to clarify this.

Due to the lack of available ancient and modern mtDNA genomes from other regions of the South Caucasus, the scholars used Armenians as a representative group of the region. Considering the low and in many cases non-significant genetic differences observed between populations of the South Caucasus, one would expect to observe a somewhat similar pattern of matrilineal genetic continuity in other parts of this region, i.e., Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Armenian Highland (partially modern day Eastern Turkey and North-West Iran).