Granddaughter thanked Armenian spy for saving her grandfather

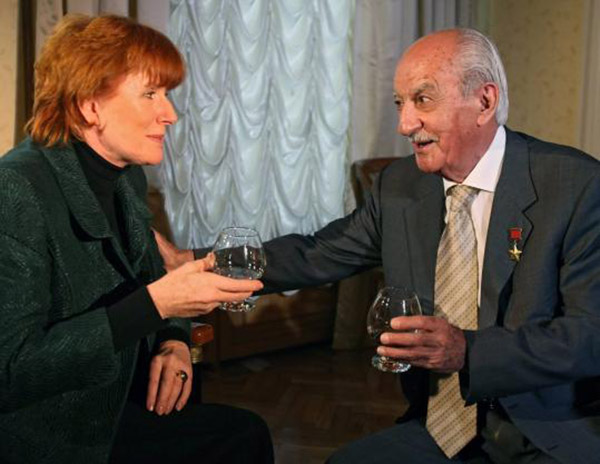

Celia Sandys, the granddaughter of the former Prime Minister of the UK Winston Churchill, expressed her gratitude to the SovietArmenian intelligence agent Gevork Vartanian for saving her grandfather’s life during the Tehran conference in 1943. Gohar Vartanian, the widow of the celebrated spy stated in a recent interview to RIA Novosti: “It actually happened in 2007. Celia Sandys paid a visit to Moscow and applied to the Press Bureau of the Foreign Intelligence Service to have a meeting with the Soviet intelligence agent. The meeting actually took place. After Gevork told her the full story, she burst out in tears and said: ‘I’m very grateful to You for saving my grandfather’.”

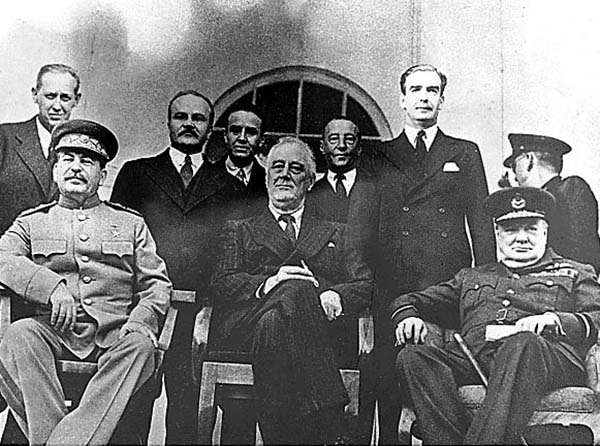

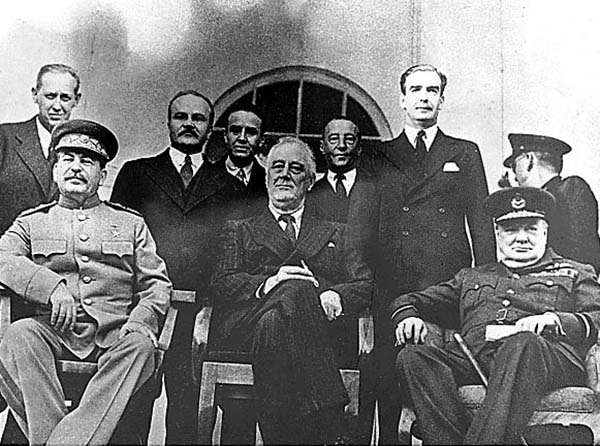

Gevork Vartanian worked for Soviet, and briefly Russian, intelligence for the best part of half a century. But his most celebrated work as a spy came at the tender age of 19, when he helped thwart a Nazi plot to assassinate Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill on the occasion of the first meeting of the “Big Three” allied leaders at the Teheran conference of November 1943.

The mission, dubbed “Operation Long Jump”, was hastily put together a few weeks earlier by Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of SS Security, after the Nazis, thanks to breaking a US Navy code, had learnt the place and date of the summit. It was entrusted to the regime’s top special agent, Obersturmbannfuehrer Otto Skorzeny, who on 12 September 1943 had led the spectacular rescue of the deposed Benito Mussolini, then a prisoner of the new Italian government.

But the scheme fell apart when Vartanian and other Soviet agents based in Iran located and captured a team of Nazi commandos who had landed on the Caspian shore. As he recounted in a 2007 interview with the RIA Novosti news agency, they were six radio operators who “were travelling by camel and loaded with weapons.” After arresting them, Vartanian and his collegeaues ordered the Nazi infiltrators to contact their superiors: “we deliberately gave a radio operator an opportunity to report the failure of the mission.”

In fact, discovery of the plot yielded a double dividend for the Soviets. Informed by Stalin of what had happened, and persuaded that travelling back and forth from the US mission in the Iranian capital could be a security risk, Roosevelt agreed to stay in a building in the grounds of the Soviet Embassy, where the conference was held. The premises were naturally bugged, and Stalin presumably gained advance knowledge of US thinking at a summit which not only decided 1944’s second front against Germany but also effectively conceded Poland and parts of Eastern Europe to postwar Soviet domination.

Born into an IranianArmenian family in the southern Russian city of RostovonDon, Gevork Vartanian was not even 16 when he followed his father into the intelligence business. Under the cover of a businessman, Andrei Vartanian had been a Soviet agent in Iran since 1930.

In 1940 the son signed on, too, under the codename of “Amir”, with the job of rooting out British and German spies.

If the SVR, the modern Russian intelligence service, is to be believed, he was a colossal success. Not only did “Amir” and his network expose 400 German agents in Iran between 1940 and 1941, he also managed to get himself enrolled at a course run by British intelligence in Teheran, training Russianspeakers as spies in Soviet Central Asia and the Caucasus. Vartanian got his training – and also duly passed on every detail about his fellow students (and future British agents) to his masters in Moscow.

Details of his subsequent career are sketchy. According to the ITARTass news agency, he graduated from the Institute of Foreign Languages in Yerevan in Soviet Armenia in 1955. Thereafter Vartanian worked in a variety of countries, including Iran, Italy, France and Greece, together with his wife Gohar, before returning to the Soviet Union in 1986. Reportedly, the couple were married and remarried several times in different places, as part of their cover.

Vartanian finally retired from the SVR, successor to the KGB, in 1992, though he continued to help train future agents. His identity was not officially revealed until 2000. “We were lucky, we never met a single traitor,” he told RIA Novosti. “For us, underground agents, betrayal is the worst evil. If an agent observes all the security rules and behaves properly in society, no counterintelligence will spot him or her. But like sappers, underground agents err only once.”

Gevork Vartanian died at the age of 87 at Botkin hospital in Moscow on 10 January 2012.

Vladimir Putin attended the funeral and paid his respects to Vartanian’s widow Gohar.

Armenpress