(The following is the text of the keynote speech delivered by G. J. Libaridian at “The Clash of Empires: World War I and the Middle East” conference, held on June 13-14, 2014 at the University of Cambridge, England, and organized by Professors Roxanne Farmanfarmaian, University of Cambridge, and Hakan Yavuz, University of Utah.)

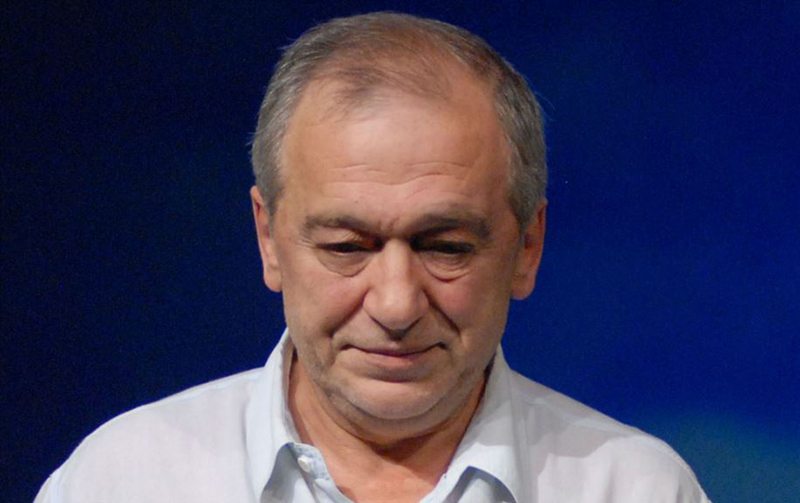

By G. J. Libaridian

INTRODUCTION

I am most grateful to the organizers of this conference and to Cambridge University for making it possible for me to present my views on a most difficult and complex subject, one that has been on my mind not only as a scholar but also as an accidental diplomat who from 1991-1997 as an advisor to the president of Armenia, dealt intensely with Russia, Turkey and Iran, and came to know their accomplished policy makers and diplomats as well as their policies.

My presentation has three parts:

1. What empires are and are not

2. Controversies in history and possible explanations

3. The fate of empires in international politics today

And I have two overriding concerns:

(1) How can we explain the fundamental differences between the opposing histories of empires and of peoples subject to empires?

(2) How can we contribute to an effort that can bring us closer to a more thorough history through which we might to learn a few lessons? Differences will always remain but even these differences should aim at enriching our knowledge and perspectives rather than neglecting, obscuring or otherwise ignoring facets of history itself.

I will also confess that my interest in this investigation reaches beyond the concern for the methodologies that sustain the social sciences and the integrity of the profession of a historian or other scholars who delve into history. My years in government spanned the last year of the Soviet Union and the first six, possibly most difficult years, of the independence of post-Soviet states. One could notice, even at that time, and can certainly do so since then, a resurgence of nostalgia for empire—albeit in different ways and to different degrees— in all three of the major neighbors of the South Caucasus: Russia, Turkey, and Iran, all three former empires whose policies had a major impact on the future of peoples and states, and still do. More on that later.

WHAT EMPIRES ARE AND ARE NOT

Let us begin with an understanding of empire, since the theme of this conference is the clash between them during the First World War. What they are and what they are not. What is to follow may seem banal and self-evident; yet given controversies regarding World War I and its aftermath and some of the historiography on that period, it appears that we need to remind ourselves of such simple truths.

Empires have occurred in history often enough that we know that they are not an exception. Empires are established through conquest and violence, not only against weaker peoples but also against other empires. Empires do not have natural borders or borders that are sacrosanct. They are not divinely ordained, however much its rulers claim otherwise. In other words empires, created by force, do not have a natural right to exist.

Though no nation, tribe, clan, race, ethnic or religious group has a natural right to rule over others, empires took themselves for granted, as the norm, sometimes as divinely ordained or legitimized by self-declared religious or civilizational missions. That is the premise and logic of the emperor—in our cases the tsar, the sultan or the shah— or of the guardians of empires. When historians of empires join in this logic and take for granted the naturalness of empires or of their borders, when they assign any sanctity or legitimacy to the shifting borders of empires at any given time, they are conferring a right to some to rule over other peoples and end up writing history abstracted from the lives of real peoples just as court chroniclers of empires and kingdoms did.

One would have difficulty finding a single principle that can account for all the changes of borders of empires. The historian who ascribes any historical legitimacy to the borders of an empire at any fixed time runs the risk of finding himself/herself at a loss when looking for the same legitimacy of borders that had been changed a decade earlier or was to be changed a decade later. Such shifts could have been even been voluntary: just think of the exchange the Sultan approved in 1878 with Great Britain: turning over Cyprus to Great Britain in return for the latter’s support in changing the Treaty of San Stefano.

This is not to say I do not understand why empires are created, always at someone else’s expense, and why they defend their borders—especially when they cannot expand it. I am arguing only that the historian must create a distance between himself/herself and the institutions she/he is studying, a methodology that underlies the social sciences.

Otherwise that historian will assign values to the parties to conflicts that were devised by the holders of imperial power and legitimize the logic of empire.

I am not sure what is the natural or ideal order of things, what political configuration provides the most viable and fair basis for legitimation of states, but empire is certainly not one of the choices. Yet history gives us many examples of empires built on a variety of principles of legitimation and of historians who have bought into that justification.

All of which does not mean that serious attempts are not being made to find new ways to build new empires. Even the simplest principles of international law, such as the right to self-determination, can be used to break up empires, as was the case with the Soviet Empire, or the start of new ones as in Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Crimea, looking at Russia alone.

As you can guess, I am not advocating the nation-state as the ideal world community system. So much has been inflicted on peoples, ethnic and religious groups, to create the nation-state and in its name. I do not believe I need to bring examples of states that, usually with violence, imposed demographic homogeneity to make populations conform to some vision of the ideal nation-state.

Nonetheless, today the nation-state is the ostensible basis of the system for international security that has been developed in the last century or more; secondly, that is the framework within which peoples still subject to foreign domination try to achieve their secure place in that same international community that tries to maintain certain standards.

It is possible to argue that I am committing a deadly sin, especially for a historian, when arguing for principles and expectations that were not at play at the time the empires were committing their sins against the peoples and groups they dominated. I will plead guilty to that charge. I am compelled to commit that sin, however, to make an important and contrarian point, because many historians are steeped in that same crime when they assess the role of empires and policies of their governments by projecting into them the norms and standards of the nation-state, norms and standards which are bad enough: I am referring specifically to the sanctity of imperial borders, concerns for the security of the empire, and the like.

One of the problems in current historiography and discussion of empire, especially in the context of the Ottoman case that impacted so much of the subsequent Near Eastern history is that which is not stated, that which is taken for granted by some scholars as a result of which the rules of the discussion constitute a very confused lot. One such unstated assumption is that it was natural for the Ottoman Empire to become the Turkish Republic of today; that, indeed, it was manifest destiny. And that anything that was done to reach those goals was not only a rational act but also a legitimate act that must be assessed by its usefulness to bring that goal closer to reality.

Although there exist organic, legal, geographic and other connections between the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey, the Ottoman Empire was not a nation-state; and standards of achievement or failure, good or evil, relevant to the creation of the Turkish Republic cannot be projected back and applied to the behavior of the Ottoman Empire in a manner that explains away, justifies or takes as a good thing anything that made it possible for the Ottoman Empire to be transformed into the Turkish Republic. We have to account for the cost of this transformation to the subject peoples and groups. History is not just the story of dominant states and dominant peoples. If the historian looks at threats to the territorial integrity of the Ottoman or any other empire as if they were late 20th century nation-states with expectations that their territorial integrity be respected, then historians should also expect those empires to have respected all conventions and treaties that we now have that protect citizens and groups within those empires in the name of citizens’, human, political and other rights. We cannot—at least should not be able to– get away with picking and choosing our principles and applying them selectively. The First World War and its aftermath cannot be reduced to the heroic struggle of what were to become “Turks” against foreign occupiers; for the Ottoman Empire it was also the conscious and planned war against many of the peoples it ruled over.

Two more considerations in this first section.

First, my reference to the use of the term court chroniclers does not apply, obviously, to all historians. There are many who have defied that paradigm and included a critique of empire in their analyses. However, the majority still abide by the rules of the court as certainly do official histories and histories taught in schools to future citizens of these states.

Second, the choice, conscious or otherwise, between being a critical historian and a court historian is often made through the use of terminology that predetermines the conclusion and tends to obviate any serious discussion of the issue. The use of terms applied to those who oppose empire as “nationalists,” “secessionists,” “rebels,” “extremists,” and “terrorists” signals not only the recognition by the historian of a central authority, which is fair enough, but also the conferring on that authority a legitimacy which that authority claimed but which cannot be assumed by the historian.

Similarly with the term “minority.” However one group was turned into a numerical majority or minority on a piece of land, a people living on their historic homeland but turned into a minority– numerically speaking— will not conceive of themselves as a minority; the sense of belonging to a land is a very personal and communal experience and cannot be reduced to statistical considerations. Analyzing authority versus subject relations with language based on the “minority” concept regarding Palestinians, Kurds, and Armenians or, for that matter Native Americans, brings about a distortion of history of monumental proportions.

Maybe it is necessary to use such terms and treat peoples in those terms to maintain, in the case of the Ottoman Empire, the myth of the immaculate conception of the Republic of Turkey. That makes perfect sense as state ideology but it has little to do with the craft of history; when such concerns are incorporated into or taken for granted in the historical analysis, we end up with bad history.

To reduce a people living on its own historic homeland into a numerical minority requires, to say the least, the application of deleterious policies over a long period of time; to do so conceptually in our writing of history requires a few words that deny such peoples their peoplehood, their right to history. It is also denial of the essence of empire—domination and exploitation— while claiming to study it and accepting its legitimacy. These approaches become commonplace and almost normal because the future of these peoples has already been taken away from them. The text that accompanied the invitation to this conference refers to the impact of “nationalist rebellions” on the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and their possible collusion with foreign powers. But it does not refer to the Young Turk and earlier Ottoman rulers who perfected policies that reduced peoples to minorities. The Ittihad ve Terakki must have known some things about nationalist rebellions that the Canadians do not know when dealing with the Quebecois or the British when dealing with the Irish or the Scots.

Such terms and assumptions take for granted the writing of history as if history is an art form that serves the purpose of legitimizing the security argument advanced by imperial rulers. And in so doing, it perpetuates the securitization of the state as an absolute value, independent of the well-being and fate of subjects or of citizens.

II. ISSUES AND CONTROVERSIES: THE TRIANGLE

Once the imperial mindset becomes dominant in historiography and in the teaching of history, we are bound to part our ways in history writing, so to speak, considering what the subjects of an empire—individuals, groups, or peoples—will remember and how they will write their history, especially when in calamitous and fateful situations these groups and people will be overwhelmed by their own victimization. May be the best way to illustrate what I mean is to discuss an issue which is still hovering over us. That which is now crassly and misleadingly called the “Turkish/Armenian issue,” a term that hides more than it reveals.

This is a multi-layered set of issues, in fact, where individual and collective memories, fundamental differences in the writing and teaching of history, and the political import of that history interrelate and affect each other.

At the bottom of the set of issues inferred by that expression you would probably find the individual Armenian meeting an individual Turk for the first time and asking a question such as “why did you kill us?” Somewhere at the top is the problem of relations between the Turkish Republic and the Republic of Armenia, that is, relations between two internationally recognized states. In between are the issues raised by scholarship on the factuality of the 1915 Genocide of Armenians by the Young Turk Ottoman government; and, the issues raised by the campaign and waged especially by diasporan organizations for the international recognition of that Genocide. As most of you are aware, since the 1970s, diasporan organizations have focused on that issue as their most important external agenda item, an issue that in a way also colors intra community agendas.

But since it all begins with what happened in history, let us look for a moment at that history. I do believe that to understand this period and the subsequent controversies it engendered, and to move beyond the inadequate paradigm of a “Turkish/Armenian” issue, we need to account for the role of the Great Powers, or the Western empires, in the events of this period. Indeed we would be unable to understand history adequately and overcome the gap between two different and opposing narratives if we left that dimension out of the equation and reduced the issues to a “Turkish” vs. “Armenian” confrontation, as simple, almost comforting for many, as it may sound.

The module I have developed to present a very complex situation in relatively simple—though I do not believe simplistic— terms is a triangle, as opposed to a straight line with two opposing ends. Each dimension or angle represents one party to the conflict: The Ottoman state, the Great Powers and the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire. The key here is to understand that each angle or each party to the conflict plays two different and contradictory roles with regard to the other two angles or parties, without implying an equality in the power and resources of each.

Allow me to explain.

The first angle or dimension is commonly known as the “Turkish” side,” that being in fact the Ottoman state and those who governed in its name, which is different from the “Turk.” On the one hand the Ottoman state was a victim of Great Power aggression persistently throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, (after, of course, the Ottoman empire itself had encroached on the lands of many European powers earlier). On the other hand, the Ottoman Empire was an empire itself. A dynasty was ruling, in the name of a religion, not only over a large number of its own coreligionists of various ethnic backgrounds but also over a variety of peoples who did not belong to that religion, tribe or clan. That rule was by definition discriminatory on the basis of religion, notwithstanding its toleration of—though not equality with—non-Muslims. As time went on, that empire also lost its sense of fairness or efficiency. It became brutal beyond the call of duty and of parameters set by Islam. Therefore empire and its regime became unacceptable to a number of groups, including many Muslim groups, even to those that had started identifying themselves as Turks and not just as Muslims.

The paths to change toward a freer society were many, the interaction and dynamics between these various ethnic and religious groups complex. This is not the place to describe these processes.

But clearly the Ottoman state emerges as both victim and victimizer. Victim of great power imperialism, and victimizer of a large number of peoples and groups it ruled over.

Now for the Great Powers. I have already alluded to their role as empires that tried to expand their influence and control at the expense of others, including that of the Ottoman Empire. They were, clearly, in the role of victimizers; there is no need here to expound on that dimension. Yet, the most liberal, enlightening and liberationist ideas of equality and freedom were produced in those countries, ideas that were liberating, that gave form and language to and legitimized the yearnings for freedom and equality of peoples and groups under Ottoman rule as elsewhere. Thus, in addition to their nefarious role as brazen imperialists, the Great Powers also appear in history as the places where science, progress and political liberalism prevailed as opposed to what characterized the empires and peoples they were victimizing: In their words, backwardness, traditionalism, unscientific if not irrational modes of thinking. Whatever the reason why these Great Powers introduced such discourse in their domestic and foreign policies, peoples in otherwise oppressed environments took words and slogans seriously. This duality of the role of Western imperial powers, as victimizer of the Ottoman Empire and as the hope for liberation of the latter’s victims, is also expressed in the different ways in which the West interacted with Armenians. Some Great Power actors were genuinely concerned with the fate of Armenians and others in the Ottoman Empire, while others merely used it to extract territories and other benefits from the Ottoman Empire. It is difficult to delineate where one begins and the other ends.

Finally, the dual role of Armenians, a people who had lived and developed a civilization for millennia in their own homeland, most of that homeland being under Ottoman rule for last few centuries. It is generally recognized that Armenians in the Ottoman Empire were at best second-class subjects. In fact that much heralded economic well-being of a segment of the Armenian population, especially in cities, has been used to ignore the utter depravity and abject poverty of most Armenians who lived in the rural areas of the provinces in historic Western Armenia/or/ the Eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire. I am referring to the underlying and fundamental agrarian issue and devastating local conditions that eventually gave rise to the Armenian revolutionary parties.

Yet in their meanderings for a savior—from reforms in the Armenian millet system to the larger Tanzimat reforms in the empire none of which provided relief— Armenians ended up with high expectations from the Great Powers, the source of the principles of egalitarianism and modern national identity. Having given up on the possibility of internal reform, in 1878 Armenians appealed first to the Russians and then to the European powers for help, the same Great Powers that were trying to dismember the Ottoman Empire, except that they could not agree on how to do it, as opposed, let us say, to the 1884 partition of Africa. It is also paradoxical that by associating with the West—a Christian West—educated, urban and active Armenians developed a sense of civilizational superiority over Muslims whom they associated with backwardness. It is possible that this was a countermeasure to the sense of superiority that even the humblest Muslim could have toward any Christian, a sense that was an integral element in the Ottoman system.

Here is what happened then and what has been perpetuated in historiography, for the most part: The Ottoman state and those in power, increasingly identifying themselves as Turks, focused exclusively on the victimizing dimension of the Great Powers, and that eventually became the basis of what is known as the “Great War of Liberation,” the founding legend of the Turkish Republic; in this context it was convenient, may be even necessary to demean the egalitarian and liberal political notions emanating from the West, to forget the nature of the Ottoman state as an empire itself with its own victims, and to confound Armenian grievances with Great Power imperialism in denial of legitimate grievances ostensibly because such grievances were used by the Great Powers. Undoubtedly many of the young Turk groups within the Ottoman power structure made use of Western ideas; but, at the end, it was the “big fish eat small fish” rationalism or social Darwinism that prevailed and determined the outcome of history, and not the part that includes liberty and fraternity and, generally speaking, equality. The Ottoman/Turkish part of the triangle looked at Armenians and other non-Muslims as allies of the victimizing Great Powers but would not see the position of Armenians as an oppressed and even massacred people who may not have had any choice but appeal to the Great Powers for help. The reason for that is that those in power in the Ottoman Empire were trying to resolve a different problem than their victims. More on that later.

By and large the Great Powers saw the Ottoman Empire as a major morsel and Armenians and others as excuses to give moral grounding to their interventions. No doubt many segments of Western societies sympathized genuinely with the plight of Armenians as victims. More importantly, it is also not always easy to see a clear line of demarcation: where humanitarian concerns ended and realpolitik inspired by imperial rivalries began. But at the end it was the imperial framework within which Armenians—the dominant Christian people in the Eastern provinces or historic Western Armenia— were placed, and that determined the policies of the Great Powers.

And for Armenians: they defined their position as the victim of Ottoman policies and their association with Great Powers and the West as a strategy for survival, if not liberation. Under the circumstances, they were not in a position to extract reforms that would have obviated the need for appeals to the Great powers and accounted for the victimization of the Ottoman Empire by their ostensible allies, the same Great Powers, especially the Russians, the French, and the British. This is not to say that there were no Armenians who understood the dual role of the Ottoman Empire, or at the least were aware of the Ottoman/Turkish state perception of the Great powers as victimizers. On the contrary. The tragedy was that the fear of imminent destruction of the economic base of the Armenian homeland and the intermittent massacres of Armenians and the unwillingness and/or inability of reformist Ottomans, including Young Turks to address the agrarian issue and lawlessness in these provinces had created an existential threat which called for some form of immediate intervention. But as we saw, for the ruling elites in that state any such intervention was seen strictly as a form of further victimization of the Ottoman state.

Thus each party played a complex role in the making of history and of its outcome but each reduced the other into a single role at the time. And we know what the result of that multiple reductionism was.

What is almost as dramatic is that historians and other social scientists studying this period have, by and large, followed the same pattern that political leaders did when making that history. I am not referring here to the controversy surrounding the use of the term genocide. That problem is limited to the question of characterization of what the deportations and massacres of Ottoman Armenians during the First World War amounted to. I am referring to the historical context within which 1915, regardless of what you call it, took place. As you are probably aware, 1915 is one of the euphemisms used to avoid the term genocide that describes the character of the policy best.

Most Turkish scholars and many others have written their works fully aware of the role of the victimized Ottoman/Turkish state but neglected its oppressive and brutal nature; at the same time, they have highlighted the role of Armenians as an excuse for the Great Powers to pursue their schemes, while ignoring the plight of the Armenians that compelled them to appeal to the Great Powers to begin with. Official Turkish historiography has created this model. But even those who have looked at the Armenian have focused largely at the victimization aspect. Yet the larger context of the social-economic crisis among the Armenian rural population that amounted to an existential threat has been ignored.

Armenian and many other scholars have stressed that same existential threat I described earlier. Yet the threat has been usually framed in ethnic, nationalist and administrative terms, rather than the socio-economic crisis that dominated Armenian discourse prior to the First World War. And most Armenian scholars have ignored the victimizing policies of the Great Powers, the same policies that were perceived by Ottoman elites and rulers as the main threat to the state they controlled, the Ottoman Empire.

Thus a good portion of the divergence in histories can be traced back to the politics of empire(s), to the one-dimensional view of the role of these different parties relative to the others.

I think we can further crystalize the conflicting renderings of history by recognizing the fact that Ottoman leaders and later the Ittihad ve Terakki and other Young Turks were trying to resolve a different problem than what Armenian leaders had in mind. The challenge to Ottoman and Ittihad leaders was: How to preserve the state, as an empire if possible, and maintain their domination of it, whatever the cost to its subject peoples. The challenge for Armenian organizations speaking on behalf of the Armenian people was, how to preserve the people, the land-based communities in their historic homeland with a minimal degree of security and well-being.

For each, it appears, it was essential that they see the other in a single dimensional framework. Still, the Ottoman state and its government at the time and its obsession with state survival were responsible not only for genocide but also for the many Muslim deaths in Anatolia by that government’s decision to enter the war. Few deaths of Muslims in Anatolia or anywhere else can be placed at the feet of Armenians at any time. Those deaths are the result of an imperial decision by a government in the name of an empire soon to become so to speak a nation-state, in the name of Muslims, in the name of Turks and whatever else the group that had usurped power could muster to pursue its war aims.

In the end, we need to look at a missing dimension of the conflict between the Ottoman leaders and Armenians. Ottoman leaders were actually very well aware of and dreaded the liberal/reformist solutions proposed by Armenian leaders for the Ottoman state—parliamentarianism, equitable representation in government for all, and administrative, agrarian and social reforms. Thus for the Ittihad, Armenians were not only an ethnic/religious dimension to their Armenian problem, but also a political one: Armenian approaches, i.e., demands for domestic reforms, constituted also a threat to the statist, conservative, military based, and Turkish nationalist state they imagined and they wanted to leave behind. That is, Armenians seen as a progressive social and political force that challenged the Ittihad/Turkish vision of the future of the empire. Armenian political parties constituted the left wing of whatever was left of the Ottoman political spectrum. Armenians constituted the last constituents of parliamentarianism in the Ottoman Empire. Paradoxically, Armenian political parties opted for empire, seeing the dangers of a Turkish nation-state, but they strove for a reformed empire. And that may have been seen as great a threat to the emerging Turkish state, as imagined by the Ittihad, as any other dimension represented by Armenians. Armenians were organized at the grass roots level, and were led by political parties that were socialistic and found salvation in liberalism and representative government.

This is a significant, if not crucial, dimension that makes the Armenian issue an integral part of Ottoman/Turkish history, rather than extraneous to it; it represents an alienation that makes possible the simplified, nationalist narratives on both sides whose narratives seem irreconcilable. How could we reconcile these divergent histories when historians ignore the attempt of Armenian political parties to integrate the resolution of the so called “Armenian Question” within the Ottoman political spectrum, within the context of the reinstatement of the 1878 Ottoman Constitution? Here the question can be raised: Who abandoned the Ottoman constitution, who, at the end was the greatest threat to the Ottoman Empire?

What we need here is a process of the integration of these narratives, at least the critical elements of the narratives that have not only diverged but also contradicted each other. What I am suggesting is a framework within which we create a distance between the narratives that are dictated by the perceptions of the actors at the time and instead is based on the complexity of history, beginning with the duality of the position of each player. Most importantly, historians and other scholars on one side should not ignore the role social-economic and the existential crisis that engendered Armenian nationalism; historians and other scholars on the other side, should not ignore the nefarious role played by the Great Powers in contributing to the crises of the Ottoman state and the criminal responses it elicited from its Turkish leaders.

I do not intend to discuss the question of different characterizations of Ottoman policies regarding Armenians during the First World War. While we need to recognize the distinction between what happened and what its casting means today, I just want to add one point to end this second segment of my talk: the campaigns for the recognition of the genocide committed by the Ittihad government beginning in 1915 and the campaign of denial of that genocide constitute a sub-text, from the historian’s point of view, of the conflict inherent in the two opposing renderings of history.

III. THE FATE OF EMPIRES IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS TODAY

All of this is not mere academic discussion. As indicated earlier, we are witnessing a nostalgic return to the idea of empire, albeit in new as well as old forms.

Most recent events have proven that the governments of these three former empires are manifesting behavior that transcends the nostalgic sentiment: in some cases they have graduated from the sphere of sentimental attachment to actual policies of re-creation, in some form or another, of empires. Particularly in Russia and Turkey we now have governments that consider their imperial heritage a positive capital that justifies their renewed attempts at domination over neighbors.

Let me also state that in my view this nostalgia is due not so much to the greatness of these empires but to the failure of the political imagination of major players on the world stage—the US, Russia, Europe and China— who did not know how to benefit from the window of opportunity for a new world order created by the collapse of the Soviet Union.

For a variety of reasons empires lose their vitality and ability to maintain the status quo. Others, with more advanced technology and resources haunt and replace them. What follows after the collapse of an empire is as important as what happened during the imperial period. Peoples, nations and states that emerge from such collapses may or may not develop a serious critique of empire; but the inheritor or victor state is often far more reluctant to be critical of the imperial tradition. After all, it is empire that secured the beautiful and sumptuous palaces and cathedrals and mosques that adorn their capitals and other cities, the ones they now take for granted and the ones tourists flock to visit; it is empire that gave them a sense of grandeur, superiority, exceptionalism and special missions or manifest destiny. To question the “naturalness” of all that may be unpatriotic; to assert that much of that wealth was the product of the exploitation of other peoples and lands and sometimes of their own people is to take the fun out of history, at least for some historians. who live vicariously the glory that was through the writing of history. While critique of empire as such has happened in societies with long traditions of democracy within the metropolis, critical assessments are rare in those who hold onto a single legitimizing narrative of their nation. Empires create subjects in their time and panegyrists; they also seem to bedazzle historians who then become, in essence, court chroniclers.

Thus it is not commonplace to find Iranian historians and social scientists with critical views of the grandeur of Persian empires; Russian scholars who question the Romanov and Soviet empires; and Turkish colleagues who have looked seriously at some of the repressive and oppressive, ultimately imperialist dimensions of Ottoman rule.

Imperial mindsets survive empires, as do imperial rivalries in collective memory, in historiography and in policy making often long after empires are gone. In fact historians become the memory makers who sustain empire, as suggested by a colleague.

Now back to the supposed end of empire.

When the USSR collapsed in 1991, it seemed to some that there now was a power vacuum in some parts of the world. Let’s take the South Caucasus, a region I know better than I know others.

So we reach the end of 1991 and there is no longer a USSR; the former superpower has been reduced to less than a third rate power, except for its nuclear arsenal, and is withdrawing militarily from the South Caucasus, though not completely. What did the other former empires, Iran and Turkey do? They sensed a vacuum and reverted immediately back to their imperial past and thought of the region as a prize to be won, a region where they could reassert their influence, even if as a shadow of their former selves.

This was the beginning of the nostalgia for empire which got nowhere because the absence of Russia in the region was a temporary setback, if not an illusion. But the imperial past was not an illusion for these two so-called nation-states. It was a model that was suggesting certain policies.

Had there been a serious critique of the imperial past of these states, there may have been an alternative model of behavior. Iranian policy makers and scholars looked upon Persian rule over the South Caucasus until 1828 as a period of benevolent government where Armenians and Muslims did not fight as they were now doing in Karabakh, where a fatherly and benevolent metropolis had managed differences wisely. And Turkish scholars argued that the Ottoman millet system had been a most benevolent system that tolerated non-Muslims to exist, as a favor, that Ottoman period was a good one, even if at the end even some of their subject peoples were denied their existence. And they implied, as did policy makers, that the extension of Turkish influence on the new republics could be the basis for peace, security and stability in the South Caucasus. Just as the Iranians had argued. Except that the Iranians had argued in favor of the restoration of an Iranian influence based on an economic common space. Turkey, more attuned to NATO terminology, promoted the idea of a common “security” space.

We know that none of that came to pass, although Iran kept an even presence in all three republics and Turkey made headways in Georgia and Azerbaijan. But at the end none of that translated into a new Iranian or Turkish sphere of influence. The latter may have happened if Turkey had resolved its problems with Armenia for the sake of greater stakes in the region.

Fast forward to a decade or more. Russia has come back with a vengeance. Not that it was absent during this period; it is just that it was biding its time, trying to find the right leader, the right moment, the right justification.

And now we have a slightly different situation in two ways. The vague notion of influence is replaced in Russia and Turkey with a genuine sense of nostalgia for the lost empires. In Erdogan and Putin we have leaders whose visions correspond roughly to the lost empires, the Ottoman and Russian/Soviet. And make no mistake about it, these are visions, fed by nostalgia but not limited to it. History—which includes the mess these empires left behind them— is being used to promote policies that are inspired by visions of empire redux in the name of whatever can be used: protection of ethnic Russians, Russian speakers, if not inherited natural rights over peoples and territories.

CONCLUSION

While this is the subject of another talk, I do feel the need to raise a question with which to end my presentation: what is the responsibility of historians and social scientists in the resurgence of imperial solutions to evaluate the present based on the past through critical lenses? Could things have been different in Russia and Turkey had historians and other social scientists been more critical assessors of imperial history, especially when educating the new generations in schools.

Let me summarize the substance of my talk. First, we do not do well as historians when we take for granted the values of the people and institutions we are supposed to study. Second, to the extent that differences in the presentation of history are engendered by actual differences in the understanding of history and not by politics, we should find ways to bridge those differences by going deeper into history, by filling in the lacunae in our knowledge and by questioning the biases in our perspectives and not by expecting that we split the difference. And third, what we say about the past may have an impact on the future; successor states to empires with nostalgic feelings and impulse for empire may be relying on us to legitimize the imperial past and justify current policies. What we say and what we write matters for the future and not just the past.

Thank you for your attention.

(The speech was followed by a brief question and answer period which will be transcribed and released as well.)