By Nora Vosbigian

1. Could you tell me a bit about the genesis of this book?

It’s sort of difficult to say when the ideas initially germinated. How far back does one go? There’s certainly a prehistory to my general interest in Armenian literature and, ultimately, in Yessayan. But, if I were to give the book a more immediate genealogy, I’d trace it back to my first queries into Ottoman-Armenian culture. I, like every other Armenian, had grown up in the looming shadow of the genocide as the be-all and end-all of Armenianness. The conception of something that could be called “Ottoman-Armenian” wasn’t even possible as I was coming of age, even though I spent much of my childhood in an Armenian village [Anjar], that’s about as close as one gets to having an Ottoman-Armenian style social milieu – minus the Kurdish/Turkish element, of course. Though, even those aspects cropped up in the local dialect or my grandmother’s preferred idiom of Turkish. By the time I was ready for graduate school in the early 2000s, I’d started to reasonably wonder what the fixation on our losses was about – I mean, what had we actually lost? What was there in the first place? I could see that my knowledge was contained by this isolationist bubble that rendered the Ottoman context into some kind of one-dimensional movie backdrop. These were actually questions of and for history, but my inclination was literature. And so, for my doctoral work, I studied a writer – Hagop Oshagan – who was obsessed with enlivening the “Remnants” – as his work’s title indicates – of that past. Soon enough, that meant addressing characterizations of Ottoman-Muslims, specifically Turks. And that initiated a whole set of other questions on Armeno-Turkish relations, inter-communal affiliations, religious conversions, etc. that had not been addressed in Armenian literary scholarship. In fact, the consensus had been tantamount to, “there’s nothing to see here,” with the purported exception of Oshagan. And I, too, for a while believed that was the case. Until, that is, I realized that much of the available scholarship was highly flawed and poorly researched, with little or no historicization.

2. So, was that the critical moment influencing the future direction of your work?

It was a vitally important moment of critical doubt. So, as I dug deeper into history, wading often aimlessly and without any guidance, just following hunches, through periodicals, bibliographies, very different pictures began to emerge. They showed, first, that Ottoman-Armenian literature is far richer, much more intellectually astute, and historically informative than its reputation has it. There’s this terrible and unfounded presumption by many scholars that this literature amounts to mere mimicry or lacks artistry and skill.

3. Could you give us an example?

One Chair of Armenian Studies once asked me at a conference why Ottoman-Armenians didn’t write anything imaginative… What can you say to that? Anyway, it didn’t take that long thereafter for me to arrive at Yessayan’s two stories devoted to Ottoman-Turkish female protagonists – [????] and “Meliha Nuri Hanum.” I knew they were important, though I didn’t quite understand why or how. But I immediately had “Meliha Nuri Hanum” translated – that was in 2011 – and shelved the two pieces temporarily as I was managing all kinds of other professional commitments. As I started developing my monograph, I returned to them, and had “Koghe” translated [“The Veil”], which then appeared in the book – Captive Nights: From the Bosphorus to Gallipoli with Zabel Yessayan – that I edited, and which was published in 2021 by the Armenian Studies series at California State University, Fresno. At this point, it was also evident to me that I needed to mine Yessayan’s work and thought to better understand the origins and significance of “The Veil” and “Meliha.” So, I began by perusing the available bibliographies and in-depth studies – notably Shushig Dasnabedian’s and Léon Kétcheyan’s – for anything and everything related to Yessayan’s Turkish associations. I should add that, some years prior, as I was doing research at the Zohrab Centre in New York, I had chanced upon an uncatalogued and unknown essay of Yessayan’s commenting on Ottoman-Muslim women’s veiling in an Ottoman-Armenian periodical. So, I knew that she definitely had an abiding and demonstrable interest in the Ottoman-Turkish sphere. I had a fairly strong inkling that there was much more to uncover. And, before I knew it, I’d amassed a dozen works, including two additional unknown pieces by Yessayan on the rights of Muslim/Turkish women. The rest was sort of straightforward. Given the exponential growth of interest – especially in Turkey and the Turkish diaspora – towards Ottoman-Armenian literature over the past almost two decades, it only made sense to make these works available to a broader public. So, I decided to translate them.

4. What do you hope to achieve with it?

Well, I hope it compels scholars and the public to take Ottoman-Armenian literature seriously. (Which also means taking the Armenian language seriously). To broach it carefully. To be attuned to its historical specifities. To respect its insights. It has been treated too often as an addendum or an ornament, or, in some cases, as an ideological platform or a conduit for voicing effectively personal persuasions. Ottoman-Armenian intellectuals were extraordinarily incisive readers and interpreters. And I think their very sudden genocidal elimination took that well-practiced and immensely valuable craft with them, leaving a vacuum in their wake. I hope this book will help reinstate that readerly acumen. More narrowly speaking, I expect the book to correct and complicate perceptions and interpretations of Yessayan’s work, which has become somewhat simplified in the public sphere. Given its thematic concerns, the book certainly also has the potential to further strengthen existing transnational and comparative literary trends. More broadly, I hope my introduction will enable those interested in these fields to enter them with a sharper focus in hopes of reforming scholarship.

5. So, what has been your journey in Armenian Studies as a scholar? How has your work been received?

About two decades in Armenian Studies and academia generally, especially in the United States, have certainly opened my eyes to many issues, not least of which has been the unchecked practice of defamation against perceived threats. I sadly became one such target of defamation. And through my readings, I’ve since realized that I’m in quite illustrious company, apparently, when it comes to the Armenian context. It’s an Armenian social practice that’s well-documented in the available literature as a source of terrible social degeneration. Even Yessayan comments on it in one of her pieces on Armenian women teachers. And it really is worth devoting a sociological study to the phenomenon. In my case, it was claimed that I was cronyistically appointed to my position at Columbia University. The fact is that I’d never applied for the job and, when I was recruited for it, I initially declined the offer. In writing. (I’m making these clarifications here, because unfortunately, there are no other disciplinary fora to articulate and redress these issues. And the stakes – namely, one’s name and professional reputation – are extremely high). Indeed, the same department that made the offer had declined my application for doctoral study two years earlier. And no one had or could have interceded to overturn that admissions decision. Just as no one had or could have interceded in any decisions to ensure my ultimate appointment. Not one of my detractors had ascertained these facts from me prior to launching the defamation, despite being given ample opportunity to do so. There were those – including righteous anti-denialist senior historians – who apparently felt that the position was “their job;” those, who were accustomed to witnessing underhanded backdoor appointments and assumed, without first checking the facts, that this was simply more of the same; and those who, out of the myriad forms of human weakness, simply could not abide the situation. Many of these individuals are or were self-avowed feminists. Most had never met me or hardly knew me. Those who did had been beneficiaries to tremendous hospitality. And several more at the helm of this vicious and entirely unprovoked assault went on to accept cronyistically or previously arranged faculty appointments themselves over the next several years. In any case, the upshot is that, like a nuclear reaction, the continuous long-term fallout has not been negligible. And, ultimately, everyone is poised to lose. I hope that readership of this book does not suffer as a result of such toxicity.

6. What are some of the other challenges you encountered in the process?

Honestly, none really, except the usual difficulties of translation. Yessayan is perhaps a bit more challenging in that, even in the Armenian, her prose can sometimes come across as a bit stale. So, keeping it alive, animated, legible for a 21st century audience required a bit more work than usual.

7. What are your hopes and plans for the study or translation of Ottoman-Armenian writings?

I guess that it be more widely read and translated, that it be interpreted on its own terms. And that eventually, a critical mass of scholars oppose the entirely unrealistic expectations of the major disciplines to make this work interesting or relevant to them in order for it to qualify as a legitimate field of inquiry or knowledge. I have to say that I’ve been especially disappointed by the hegemony of the margins – namely, leftist Postcolonial Studies –, which keeps insisting that we “uncolonized” others use its terms and frameworks if we hope to stand a chance of being heard. Maybe it’s time we decolonize ourselves of the decolorizers.

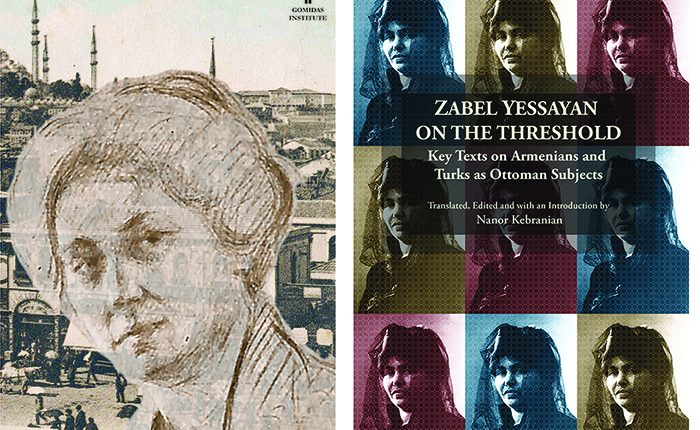

* Dr. Nanor Kebranian is a researcher, writer, and translator working at the intersection of history, literature, and law. She received her doctorate from Oxford University. Her latest publication is “Zabel Yessayan on the Threshold: Key Texts on Armenians and Turks as Ottoman Subjects” (London: Gomidas Institute, 2023).