Recently, the Italian journalist Federico Nastasi accompanied by photographer Mauricio Zina, visited the Armenian community of Uruguay for their special travelers column “Dossier,” featured in the Italian magazine Missioni Consolata. The following is a translation of the Armenian segment in their latest column.

For the Armenian Community of Uruguay, a Welcoming Country

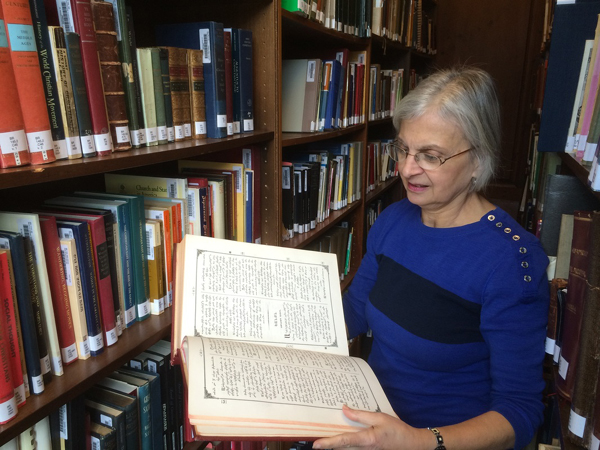

“I’m Armenian,” Silvana, a bookseller in the Ciudad Vieja of Montevideo, tells me in her Rio-Plateau Spanish. Silvana, although she was born in Uruguay, does not speak Armenian and has never set foot in Armenia, she cares about her identity. And like her there are about fifteen thousand Armenians in the country, grateful to Uruguay for being the first country in the world to have recognized the “Medz Yeghern”, the Armenian Genocide, with a law in 1965.

Between 1915 and 1916, the Ottoman Empire, led by the government of the “Young Turks,” planned and carried out the deportation of the Armenian population from its territory, authorized by the Tehcir Law of May 29 1915, resulting in the death of one and a half million Armenians. On the night of April 23–24, 1915 in Constantinople, in an operation that beheaded the Armenian intelligentsia, more than a thousand journalists, writers, poets, delegates to parliament, were deported to the interior of Anatolia and massacred along the way. In the death marches, which involved 1.2 million people, hundreds of thousands died of starvation, illness or exhaustion. The males of the families, adults and children, were murdered, and the women dragged through atrocious forced marches and prison camps.

Despite the exodus and photographic evidence of what happened, Turkey does not recognize what many historians call the first modern genocide, based on the ‘scientific’ planning of extermination.

In 2016, on the occasion of the centenary of the Genocide, Pope Francis visited Armenia, condemning the Genocide and prayed to prevent this tragedy from happening again. During his visit to Yerevan, he stressed that memory could be a “source of peace” to bring the two countries on the road to reconciliation.

The country asking for migrants

In the 1920s and 1930s, Uruguay was a proponent of immigration: Italians, Spaniards, and even seven to eight thousand Armenians arrived. They started from Lebanon, France or Syria. They had grown up in orphanages, because genocide had already taken place. “They were lost, they had no idea where they had come from, they had nothing in their hands,” Diego Karamanukian, an intellectual from the Armenian community of Montevideo, who speaks fluent Armenian and runs Radio Arax, an Armenian cultural radio program, tells MC.

How is it possible that, after a century of genocide, four generations and 13 thousand kilometers away from the site of the events, Armenian identity is still so strong on the north bank of the Rio de La Plata? “I grew up with horror stories from my grandmother, who was a servant of a Turkish family. She came here not to look for work, but to avoid getting killed. Dealing with this identity is a response to the denial of the genocide that continues to this day,” explains Daniel Manuelian. He and Diego are leaders within the Hunchakian party, the Armenian Social Democratic Party present in many countries, including Lebanon, the USA and even Uruguay. For this interview, they receive us at Casa Armenia, a beautiful building with a garden in the residential district of Prado, in the west of Montevideo. It is the seat of the party, a place of culture, sports and parties.

“It is incredible to think how a group of people, who arrived covered only in rags, in a short time not only found work and started families, but organized the community, founded schools, churches, associations, newspapers, radio stations, choirs, and music festivals. They cultivated the identity persecuted by the Ottoman Empire, they saved it from oblivion”, Diego proudly reasoned, describing the activity of the first Armenians of Uruguay. “They arrived knowing that there was no return ticket, they built here the homeland they had lost. They gathered around the center of Montevideo, where there were industries. And maybe there’s also a geographical and nostalgic reason: they went there because they were looking for the mountains of their country,” Diego continues. The first arrivals, at first, worked as laborers, in activities that did not require knowledge of Spanish. Then, they dedicated themselves to small trades and shops, to the almacenes. In the old buildings in the western part of the city, there are still signs in Spanish and Armenian. Former President Tabaré Vazquez said that in his neighborhood, La Teja, his family, in a period of tightness, had received help and food from an Armenian trader.

“Here the Armenians have made themselves loved and have contributed to the construction of the country. We did not ghettoize ourselves, on the contrary. First of all we are Armenians, but we are Uruguayans: we cheer Nacional and Peñarol (the two most followed football clubs in the country), we have seen Uruguay twice world champion. Our cuisine has mixed with Uruguayan cuisine: here you can eat a delicious lehmejun (a kind of Armenian pizza) with the addition of local mozzarella. We have received welcome and recognition: in Montevideo you can walk on Rambla Armenia, there are monuments and plaques reminiscent of genocide, and April 24th is Remembrance Day. If you say in Armenia that you are Uruguayan, the doors open to you,” Diego explains.

Defending Armenian identity

“It’s denialism that angers me. I am living proof of genocide. If (genocide) didn’t exist, I just wouldn’t be here. A psychologist explained it to me: we care so much about our identity because ours is an unrecognized trauma,” Daniel says. But today, the identity of the community in Uruguay is at risk: “My son does not speak Armenian, he does not care much about history, he does not experience my own trauma. But if they shout “Armenian” on the street, he turns around. It’s the fourth generation, identity is lost over time,” Daniel confesses somewhat disheartened.

“In Lebanon, Turkey, Syria, Armenian identity is maintained through the Orthodox Christian religion: being Armenian is a way not to be Muslim. Here in Uruguay, such a secular country, the religious issue is not confrontational. So it’s harder to cure identity,” Diego reasoned. He continues a little melancholy: “Language is a problem, it is difficult, few speak it and very few teach it, it is no longer spoken in the family.” But then he has a flick: “Sometimes curiosity rises again. There are those who take online Armenian courses, now there is also a university course. And then, with the Internet, many people follow the news of Armenia, as now with the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. Identity is fading, but it won’t go away. Identity is will,” he concludes with a little hope.

Federico Nastasi