By Orhan Kemal Cengiz

Translator Sibel Utku Bila

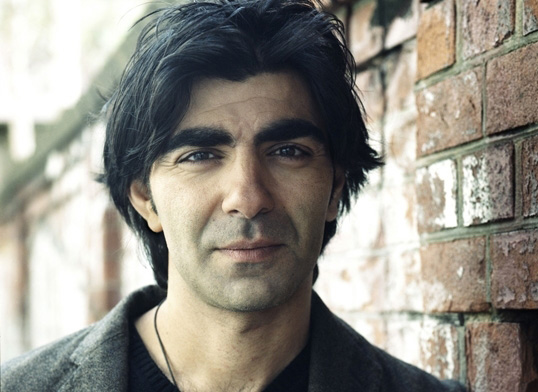

German-Turkish director Fatih Akin and the bilingual Turkish-Armenian weekly Agos have been receiving death threats from nationalist Turks since Agos interviewed the director about his new film last month. The content of the messages, the outpouring of support for the threateners and the authorities’ inaction come as a grim illustration of the current atmosphere in Turkey. The death threats are an omen for the coming year, the 100th anniversary of the Armenian genocide.

Akin — the director of films such as “Head-On,” “Crossing the Bridge: the Sound of Istanbul” and “Soul Kitchen” — gave a long interview to Agos on July 30 about “The Cut,” his new film that focuses on the Armenian genocide. The interview was received with great interest and contained intriguing revelations.

For instance, Akin said he considered making a film about the life of Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, the former Agos editor who was assassinated in 2007, but none of the Turkish actors he approached would take the role.

Akin then began to work on a new project: the story of a Turkish Armenian who embarks on a worldwide search for his daughters after surviving the 1915 massacres. Akin wrote the script in German, but later decided to shoot the film in English. He sought help from Mardik Martin, an American screenwriter with Iraqi and Armenian roots who has contributed to the scripts of Martin Scorsese films. According to Akin, Martin not only translated but modified and “intensified” the script.

The film — starring French actor of Algerian origin Tahar Rahim and Turkish actor Bartu Kucukcaglayan — was shot in Jordan, Cuba, Canada, Malta and Germany. It is scheduled to premiere at the upcoming Venice Film Festival, and only a trailer is currently available.

Akin told Agos he did not consider “The Cut” a film about the Armenian genocide but rather an adventure movie. He said he had no political motives in making the film and hoped it would “receive due respect in Turkey and be shown in large, modern theaters.”

Akin was aware his film would not be treated as just another movie in Turkey, even though he did not see it as the genocide. “The Cut,” after all, is the first film by a Turkish director that addresses the events of 1915. The director, however, remained optimistic that the film’s showing in Turkey would be trouble free. “I’m confident that the Turkish people, to which I belong, are ready for this film,” he told Agos.

Yet as soon as the interview was published, a tweet by the ultra-nationalist Pan-Turkist Turanist Association suggested that Akin might have been overly optimistic.

The message read, “Efforts are underway, under the leadership of the Agos newspaper, for the screening of Fatih Akin’s film about the so-called Armenian genocide, ‘The Cut,’ in Turkey. ‘The Cut’ is the first leg of a plot to make Turkey acknowledge the Armenian genocide lies ahead of 2015 and we … will not allow it to be screened in Turkey. We are now openly threatening the Agos newspaper, Armenian fascists and the self-styled intellectuals. That film is not going to be shown in a single theater in Turkey. We are following the developments with our white berets on and our Azeri-flagged glider. Let’s see if you can!”

The “white beret” metaphor carries a sinister message. Ogun Samast, Dink’s suspected assassin, wore a white beret when he shot Dink in the neck outside the Agos office in downtown Istanbul on Jan. 19, 2007. The white beret has since become a symbol displayed frequently at anti-Armenian racist and nationalist demonstrations.

The Turanist Association’s threat received a series of supportive messages by other ultra-nationalist groups on social media.

The ensuing events demonstrated that the Turkish authorities haven’t learned their lesson from Dink’s murder, which was preceded by similar threats. Under the Turkish penal code, those messages constitute a criminal offense on several grounds, from containing threats to spreading hate speech. The prosecution of these offenses does not require a complaint by injured parties. The law automatically entitles prosecutors to launch probes. Sadly, hate speech against minorities fails to attract prosecutors’ attention.

In remarks to Al-Monitor, Agos editor-in-chief Robert Koptas said the publication has become used to receiving threats, describing the authorities’ inaction as the norm. “For us, this is not an extraordinary situation. And the fact that it is not extraordinary is in itself an indication of what an atmosphere we live in,” he said.

“We had to file a complaint this time again, though the police and the judiciary were supposed to have already taken action. We are not asking for any special protection, but we are a publication whose editor-in-chief was murdered outside his own office. Thus, the threats we receive are supposed to have an extra meaning for the police and prosecutors,” Koptas said. He added that no government official has called him about the threats or made any public statement on the issue.

The threats indicate that certain tensions and troubles are in store for Turkey in 2015, the centenary of the Armenian genocide. The debate on the Armenian genocide in Turkey in recent years has become as free as never before. Commemoration events are now held across Turkey on April 24, the genocide remembrance day. Yet the latest incident suggests that ultra-nationalist groups are in a state of alert as the anniversary draws near.

The threats directed at Akin’s film demonstrate that some quarters in Turkey have lost none of their intolerance and, emboldened by the judiciary’s failure to act, feel free to target anyone they like. It seems no lessons have been learned from the past.