By Emma Sinclair-Webb

International Herald Tribune

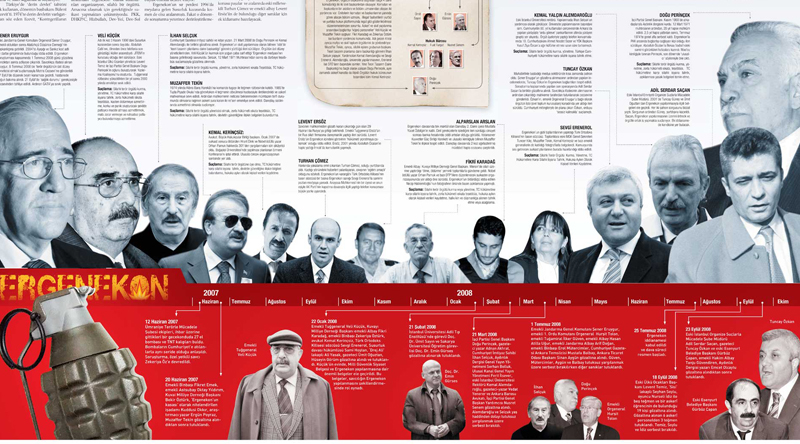

The sentences handed down Monday by the Istanbul Heavy Penal Court No. 13 against 275 defendants in the “Ergenekon trial” brought to a close perhaps the most politically divisive trial in Turkey’s history.

The defendants (66 of whom were in prison at the time of the verdict) received a range of long sentences, including life imprisonment, with the vast majority convicted of aiding and abetting or membership in a “terrorist organization” (the “Ergenekon” gang), which plotted coups against the government in 2004.

Those convicted include retired and serving military personnel, academics, journalists and some organized crime figures. Defendants are likely to appeal their sentences all the way to the European Court of Human Rights.

The Ergenekon trial played an important role in efforts to lay to rest a history of military meddling in democratic politics. Much of Turkey’s modern history has been dominated by a secularist military-bureaucratic alliance that regularly derailed the democratic process when confronted with governments or political movements that threatened its political control.

But while the trial was a milestone in civilian control over the military, it was lacking and flawed in other respects. One missing element was the failure to investigate evidence of much wider involvement by some of its key military and police defendants in a longer history of unlawful and criminal activity in Turkey, or in serious human rights abuses against the civilian population.

In particular, the court failed to look into allegations that a core group of defendants was responsible for serious human rights abuses in the areas of the country where they served in the 1980s and 1990s: torture, and thousands of enforced disappearances, killings and illegal village evacuations in the southeast, as well as political assassinations in the western part of the country. The trial also failed to look at these defendants’ possible involvement in clandestine networks connected with the state in much more recent political assassinations, such as the January 2007 murder of the journalist Hrant Dink, or the April 2007 killing of three Christians in Malatya. One defendant, Hursit Tolon, is on trial separately in connection with the Malatya murders.

The Ergenekon proceedings were also overshadowed by concerns about the fairness of the trial. These ranged from questions about the flimsy nature of evidence against some defendants, the implications for media freedom arising from the prosecution of journalists as coup plotters, concerns about the appropriateness of the application of terrorism charges, objections to the misuse of protected witnesses, which impeded the defendants’ ability to challenge the evidence against them, and in particular the prolonged pretrial detention of some defendants. Some saw the trial as no more than a witch hunt by the governing A.K.P. against its political opponents.

There was an opportunity to prove those critics wrong by ensuring a scrupulous commitment to fairness throughout the process. But as with many trials, that opportunity was missed.

Over the years human rights groups have repeatedly expressed serious concerns about the fairness of trials in Turkey, in particular those held in special courts dealing with terrorism and organized crime. Such courts and trials follow a practice of virtually mandatory pretrial detention for extended periods. So although these are not new concerns, they have deepened with the proliferation in recent years of “mass trials” — with multiple defendants alleged to have been part of terrorist groups. The thousands of people on trial for alleged membership in the Union of Kurdistan Communities and association with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party face even less fair proceedings and flimsier evidence, with a large number still held in prolonged detention pending verdicts.

The A.K.P.-led government has adopted a series of “judicial reform packages” aimed at mitigating the worst abuses. Yet the broad and vague nature of “terrorism” offenses and the use of special courts to try these cases have left the problems largely in place.

From a human rights point of view, a key disappointment of the Ergenekon trial was that it did not represent progress toward holding public officials, military, police and civil servants accountable for their actions in a way that will resonate with the public across the political divide, and that it did not serve to promote a more democratic culture.

While crimes against the state continue to be punished severely, Turkey is still a country in which ordinary people face huge obstacles to securing justice in the courts for crimes committed by state officials. For the victims of those abuses, the Ergenekon trial means little.

Emma Sinclair-Webb is a senior Europe researcher at Human Rights Watch.