By Arthur Hagopian

SYDNEY — His home in Sydney’s high-end Chatswood suburb is a far cry from the ramshackle camp in Greece where his family had found refuge from the 1915 Turkish massacres and where he grew up, and he no longer goes hungry or unshod.

But Chris Dikian still bears the psychological scars of the battle for survival he waged as a youth during the Nazi occupation of that country.

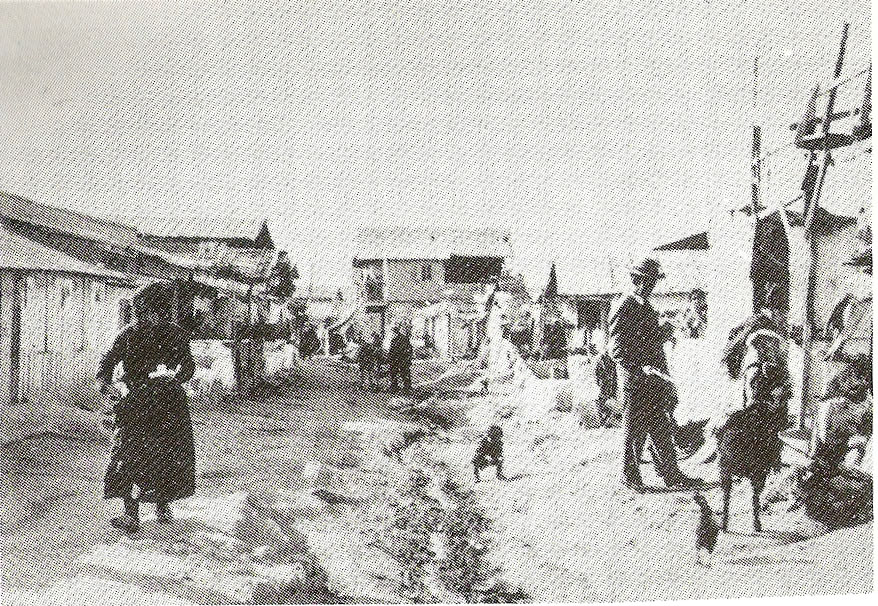

“Phix-Derghouty was a camp of mud brick shacks with tin roofs that housed mostly survivors of the massacres from various parts of Western Armenia,” he recalls. A line of red brick buildings stood at the edge of the camp, opposite a Bata shoe factory, with an empty field in between.

Some enterprising souls had turned the field into a vast marketplace and shopping center, crammed with barbershops, smithies, a pickles factory, restaurants, cafes, bakeries, smallgoods and second hand dealerships.

Some had even rigged up power lines. The unlucky others, like the greengrocers or fruit vendors, had only kerosene lamps.

“This was the heart of the camp where the good and bad mixed,” Dikian recalls.

“At dusk, the smoke from the souflaki stalls combined with the aroma filled the air.”

The shed housing his family was located near those shops. Like the other camp dwellings, it had one large all-purpose room with a storeroom underneath where the family kept their precious hoard of food: olives, cheese, flour, corn, olive oil.

“I don’t remember it having a kitchen. But all the mouthwatering smells came from next door where my grandmother used to live. She had arrived in Piraeus with her daughter and son and had ended up in the camp. My grandfather was said to have been a doctor who had migrated to the US having had enough of Sultan Abdul Hamid,” he adds with a chuckle.

Dikian’s father was born in a town near Istanbul to a rich business couple but all efforts at recovering any of their fortune proved abortive.

Dikian tells how his father and uncle became separated from the main refugee caravan and ran to the nearby hills.

“They were saved by some Kurds and became part of their community as shepherds. With their newly adopted Kurdish family they moved from one place to another looking for green pastures, as is the Kurdish custom,” Dikian recounts.

But the two brothers lost track of each other again. The uncle managed to return to Armenia after months of wandering, but his father ended up in a red cross center, and eventually found his way to mandated Palestine where he settled.

Another uncle, Leo, had set up as a vegetable vendor and went about the streets with his merchandise piled on a 3-wheel cart.

“In the evenings, the eerie light from the kerosene lamp hanging from a pole on the cart, evoked childish terrors in me,” Dikian remembers.

A resourceful and helpful man, Leo enjoyed partying and one day, during the Italian occupation of Greece, he had the temerity to plan an anti-Mussolini record on his portable gramophone, a misdemeanor that earned him a six month tenure in a prison on Crete.

“He must have been drunk,” Dikian surmises. “But he survived the harsh conditions in prison and came back loaded with dried figs and other fruits and sporting a beard.”

“The Italian occupation did not last long. Soon the Germans moved in and unlike the British who liberated the country, they brought misery, hunger and atrocities with them,” he recalls.

To combat the war-time famine, the Germans instituted a food rationing system but it did little to assuage the refugees’ pangs of hunger.

“I and my grandmother sometimes climbed the nearby hills where on the slopes we would find and collect edible plants to cook. And sometimes my father would lug a sewing machine or some valuable household item to the outlying villages and barter for olive oil, flour, olives, wheat, cheese, anything he could get his hands on. But the less fortunate found themselves lucky if they could get hold of a dog and cook it and eat it.”

People were dying around him all the time.

“All day long, we would see the garbage trucks making their rounds and collecting dead bodies from the streets and without ceremony carting them away.”

Although the Greek resistance fighters did put up a fight, and no German soldier wandering around was safe, retributions were severe: for every soldier killed, the Germans shot 10 civilians they picked at random. In time, they upped the ante to 100.

“Schooling was irregular and we children had a lot of time on our hands. We wandered inside the known and unknown areas of the camp. We were advised not to eat the chocolates wrapped in shining silver and gold paper dropped by the German planes. The Germans were at liberty to poison us but once a man tried to sell adulterated olive oil, and they hanged him. Nazi justice,” Dikian adds.

One of the most memorable sights around the camp was that of Jews wearing their yellow patches. Dikian remembers there were quite a few of them, but gradually their number died down.

When the Germans succeeded in uncovering weapons caches, all hell broke loose.

“Peeking out of our window, I once saw a man – he must have been a resistance fighter – leading German soldiers to a ditch near our house where some weapons had been hidden. Rivers of blood ran down the man’s face. After they had dug out the weapons, the soldiers rewarded their informer with a bullet in the brain.”

One day, he woke up to the shrieks of people and the suffocating smell of fire.

“The Germans are leaving!” people were shouting in jubilation.

“They were indeed, but before they left, they conducted a mopping up operation, shooting some people and herding others, my father among them, into train wagons.”

And then they set the shops on fire with their flamethrowers. As the smoke rose into the sky, people ran around like headless chickens trying to save what they could.

“I stood at the train station, holding my mother’s hand.

“‘Where are they taking father?'” I asked her.

“‘God only knows,'” she whimpered.”

The arrival of the British troops heralded a new dawn of hope for the camp dwellers.

“We sensed, right from the beginning, that they were different, more humane than the dour and atrocious Germans. The moment the smiling Tommies set up camp, we clambered around the barbed wire asking for handouts. Unlike the German soldiers who would respond with a kick when we asked for food, the British almost always managed to find something for us.”

“George! George!” the children would call out the moment they saw one of the British troops coming out of their camp. It was their universal affectionate name for them.

The soldiers, most of whom were young, liked to sunbathe on the flat roof of their headquarters building. Sometimes, they would reward their faithful audience with biscuits they threw into the air.

“We collected every morsel,” Dikian recalls.

Sundays were special. The soldiers got the children to line up and then led them to their mess hall for a feed: “what an unheard of luxury that was – hot tea mixed with milk, beet root, fried eggs, white delicious slices of bread.”

Soon afterwards, Dikian’s uncle Leo reappeared, this time with a horse wagon.

“After some discussion he put me next to him and we drove away. He wanted to show me the world beyond the barbed wires. I stayed for a short time with him helping him with odd jobs and then returned to Phix-Derghouty to find myself head of the family with my father away.”

“I got hold of a couple of cartons of Papastrato cigarettes and set myself up in business selling them wherever I could, mostly in the tramways. I was doing all right too until the day I got robbed. Then I started to sell cakes but the business floundered when I started getting hungry and eating the cakes.”

“Then came the joyous day when my father walked in through the door – he had been freed by the Russians, and now began making plans to move us all to join his sister in Jerusalem.”

Phix-Derghouty was left behind – but never forgotten. When Dikian returned for a visit several years later, there was no trace of the camp: in its ashes, the phoenix of a swank new suburb, Neos Kosmos, reared its golden head.

PIX captions:

A scene from the Phix-Derghouty camp

Chris Dikian

The tramways at Neos Kosmos