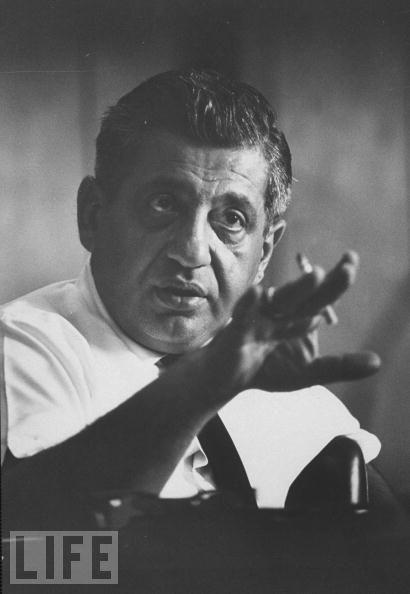

Zorthian, 90, died Thursday in Washington, D.C., hospital where he had been admitted a few days earlier, his son Greg said. A staph infection was the immediate cause of death.

By his own reckoning, Zorthian was the last surviving member of the original cadre of U.S. diplomats and military leaders whose policy decisions shaped events in America’s longest war.

Dispatched to Saigon in 1964 by President Lyndon Johnson to defuse an increasingly acrimonious relationship between American officials and news correspondents covering the war, Zorthian used a mixture of charm, sly wit and uncommonly straight talk in trying to establish credibility for the U.S. effort.

In the first American war without formal censorship, Zorthian had no way to prevent unauthorized disclosures or stifle criticism, but he refused to be intimidated by either officials or the news media.

Zorthian’s candor earned him grudging admiration and respect among the journalists who were his primary adversaries. While coming to trust his word, some also found him a tough competitor at the poker table.

Many ex-Vietnam correspondents who dealt with him say Zorthian, more than any other government spokesman of recent memory, understood and valued the role of the press in a free society.

“In postwar years, Barry Zorthian remained steadfast to his conviction about the significant role the media must play in a democratic society,” said Peter Arnett, a Pulitzer Prize-winning war reporter for the AP in Vietnam and later a CNN foreign correspondent. “His patience was tested in Vietnam, but he understood the principled motivations of the journalists working in Vietnam.”

Arnett recalled that when he complained about an American military policeman threatening to shoot him during a 1965 Buddhist street demonstration in Saigon, “Zorthian shook his head in mock concern, and said ‘Damn it, Peter, you threatened him and he was just responding.’ ‘What?’ I replied. ‘Yes,’ Barry said, ‘you were aiming your pencil at him and that’s more dangerous around here than a .45.’”

Zorthian remained proud of his most controversial achievement — creating the daily Saigon press briefings that became known as the “Five O’Clock Follies,” where officials delivered battlefield summaries and answered questions from reporters.

Though they sometimes became shouting matches and were widely ridiculed, the briefings lasted a decade, the only regular forum in which U.S. and South Vietnamese officials spoke entirely on the record and were often challenged or contradicted by reporters, sometimes to their embarrassment.

“I can never recall him misleading me, even though he straddled a fine line of loyalty to the government and the public’s right to know, which he strongly believed in,” said George Esper, a former AP Saigon bureau chief now teaching journalism at West Virginia University. “He was always accessible and always knew what he was talking about.”

Zorthian was born of Armenian parents in Kutahya, Turkey, in 1920. The family immigrated to the U.S. and New Haven, Conn., where Barry attended Yale University, edited The Yale Daily News and was a member of Skull and Bones.

Graduating in 1941, he served as a Marine Corps artillery officer in the Pacific war and retired to the USMC Reserves as a colonel.

After a postwar stint at CBS Radio, Zorthian spent 13 years with the Voice of America, reporting on the Korean War and rising to program director. He then did tours as a foreign service officer in India and Vietnam.

In 1964, he was chosen by then U.S. Information Agency director Edward R. Murrow to run the Joint U.S. Public Affairs Office, which dealt with the news media. After a year, he was given the diplomatic rank of minister.

In that capacity Zorthian served as press media adviser to three successive U.S. ambassadors to South Vietnam — Henry Cabot Lodge, Maxwell Taylor and Ellsworth Bunker — and to Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the U.S. military commander there.

From 1968 on, Zorthian worked in the private sector, including 12 years as president of Time Life Broadcast and Cable and then as its vice president for government affairs in Washington.

Most recently, he worked in media affairs for Alcalde & Faye, a media consultant firm based in Arlington, Va.

In addition to his Yale degree, Zorthian had a law degree from New York University.

Zorthian’s wife of 62 years, Margaret Aylaian Zorthian, died in July. He is survived by two sons, Greg and Steve, a daughter-in-law and two grandchildren.

Barry Zorthian, Press Officer in Vietnam War, Dies

- No comments

- 4 minute read

Pashinyan’s Visit to Turkey and Beyond

By KRIKOR KHODANIAN At the invitation of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan,…

- MassisPost

- June 29, 2025

- No comments

- 3 minute read

“I Still Can’t Believe What Happened on June 20”

By LUSYEN KOPA Exactly three months ago, I wrote an article titled…

- MassisPost

- June 26, 2025

- No comments

- 4 minute read

Anniversary of the Immortality of the Twenty Hnchakian Heroes

By KRIKOR KHODANIAN 110 years ago these days, the prominent figures of…

- MassisPost

- June 15, 2025

- No comments

- 3 minute read

The Eternal Memory of the Twenty Heroes

By BARKEV TAVITIAN Every year on June 15, the global Hnchakian family…

- MassisPost

- June 13, 2025

- No comments

- 3 minute read