By Amos CHAPPLE

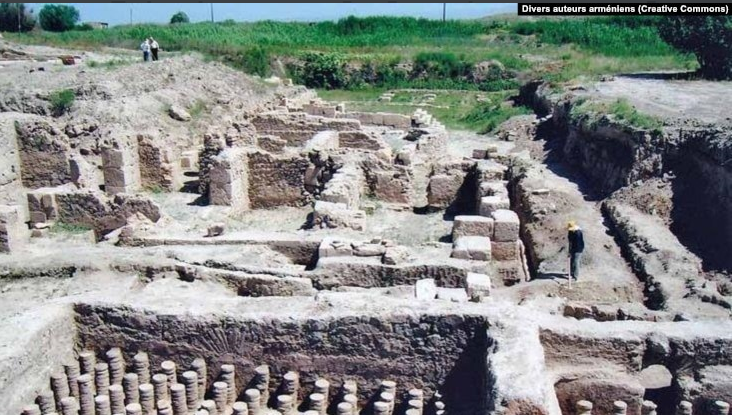

After moving aside a jumble of ripening melons, Armenian and German researchers uncovered a thrilling find with their shovels in the summer of 2019: Just 30 centimeters below the surface of the Ararat plain lay a massive slab of Roman concrete.

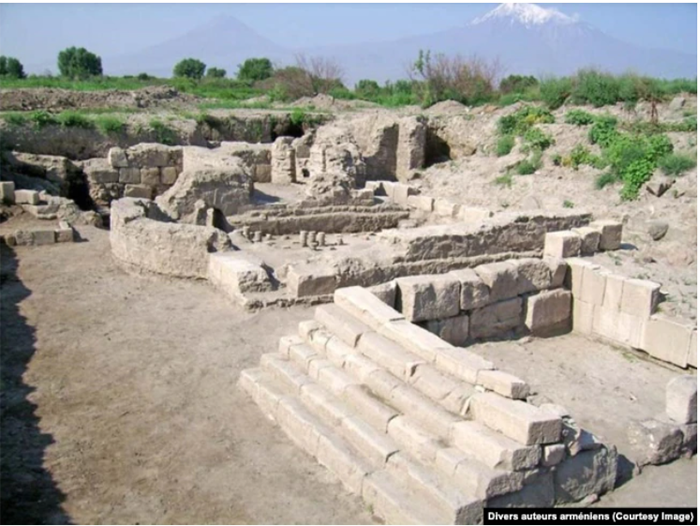

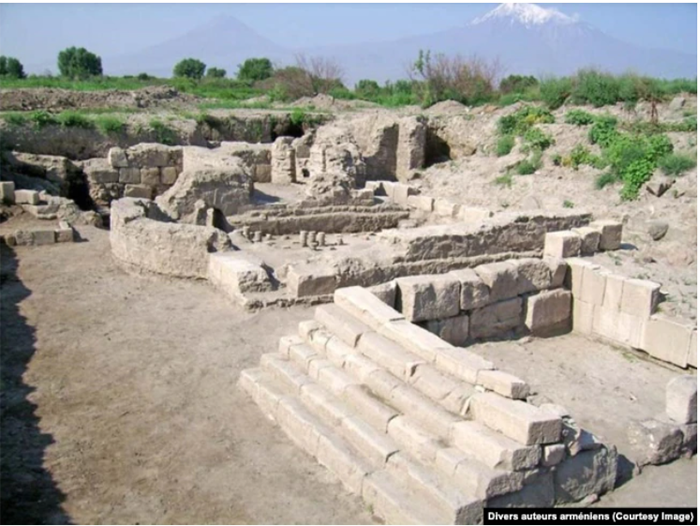

The block is believed to be one of hundreds of foundation stones from an unfinished Roman aqueduct intended to funnel water to the ancient city of Artaxata. Although the original source of the water for the aqueduct is not known with certainty, its length is calculated to have been around 31 kilometers and may have begun near the Temple of Garni.

Rome controlled the former Armenian capital of Artaxata, located around the hills where the Khor Virap monastery is located today, for just three years before retreating west in the face of a local uprising in 117. The aqueduct’s construction was abandoned and all trace of it eventually disappeared beneath centuries of shifting soil and dust.

The results of the 2019 dig were published in November as a joint project between the Armenian Academy Of Science and the University of Munster. Achim Lichtenberger and Torben Schreiber, who authored the report with Mkrtich Zardarian, told RFE/RL that the first clue about the Roman Empire’s easternmost aqueduct came in 2018.

Using magnetic surveying equipment, researchers that year spotted a mysterious underground line that led directly to one of the hills where the ancient city stood.

The archaeologists gathered together that evening to study the geomagnetic survey results in a house where they were based.

“It was an amazing moment when we were looking at the raw data from the survey and thinking, ‘What could this be?'” Lichtenberger says. “We were considering everything from a Soviet water channel to an aqueduct.”

A year later, the team was able to reunite and, with the blessing of the farmer who owned the land, dug up the remarkable find. But the researchers say that anyone hoping to lay hands on the freshly discovered Roman concrete will be disappointed.

“You won’t see the remains of this aqueduct,” Lichtenberger says. “After our excavation, we backfilled everything.

“We do this because it’s the best way to protect the ancient ruin from the weather and everything, and it means the farmers can use their land again within a year.”

The German researchers say the excavation, which involved living and working alongside Armenian colleagues and German students, was one of their most memorable assignments.

“When you have a campaign like this that lasts for six weeks, it really becomes like family,” Schreiber recalls. “It was a very friendly dig.”

Amos Chapple is a New Zealand-born photographer and picture researcher with a particular interest in the former U.S.S.R.

RFERL.org