By Zeina Antonios

Sitting in front of his workshop on Armenia Street in Beirut, Yervant Balian has an eye on passers-by and another on his employees. In the neighborhood, this silversmith, who has operated for 68 years, is known as Master Yervant.

It is only this year that he has stopped operating the machines himself, but he continues to oversee the manufacture of the silverware that comes out of his workshop. One way, perhaps, for this man who has been working from a young age to prepare for retirement. “I am tired. 86 years is a lot,” he says with a sigh. Yervant manufactures silver tableware, candlesticks, and copper kettles. But his specialty is the cups and medals that are awarded in all the championships in the region. “I’m the only one in Lebanon to make these cuts,” he says. I export them to the Gulf countries. But more and more people are now buying cuts made in China, while they are of poor quality.”

Master Yervant also supplies wholesale parts to Lebanese traders, including Tripoli, Tyre, Saïda and Bourj Hammoud. “The cutlery and copper utensils that you find in most of Gemmayze’s restaurants today come from my home,” he says, quite proud of his company, rising to the sweat of his brow.

At 86, Yervant Balian is without a doubt one of the oldest active silversmiths in the country. He learned this trade on his own, after having joined an aluminum product manufacturing plant when he was 17 years old. Today, Yervant is one of the pillars of Armenia Street, a neighborhood of which it is the living memory. Not surprisingly, everyone knows him in this street, and he considers himself, because of his advanced age, as “the father of all.”

At the age of six, in 1939, just after the Second World War, Mr. Balian arrived in Beirut with his parents. His father, a worker, was struggling to make ends meet and raising his four children. “When we arrived in Lebanon, we settled in Armenia Street, in a one-bedroom apartment. Since then, I have never really left here,” says the craftsman. His father could not afford to provide education for all his children, Yervant, who was born in Alexandretta (Iskenderoun) in [today’s] Turkey, had to leave school, and spends his days scouring to make money by selling chewing gum. “I made more money than my father at the time, just by selling my chewing gum! At first, he was afraid that I was flying,” recalls the old man. “I could have gone wrong,” he admits today. But at home, it was not allowed, I had to either learn a trade, or go to school. My brother was able to study.”

Multilingual and a Globe-trotter

In his workshop is a photograph of Andranik Ozanian, commander of the Armenian army and figure of the struggle against the Ottoman Empire in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “Andranik Pasha is a hero! My uncle fought with him,” says Yervant proudly. This uncle, the silversmith, was able to meet him a few years ago … in Azerbaijan, and at the moment when he least expected it. “During one of my trips to Armenia, during the Soviet Union, I learned that my uncle was still alive,” says Balian. I finally traced him to Baku, Azerbaijan, and I went to see him. The following year, I went back to visit him with my wife.”

Master Yervant traveled a lot in his youth. And despite the fact that he had to leave school at a very young age, the octogenarian is multilingual. “In addition to Armenian, I speak Arabic, Turkish, Polish, French and English. I have traveled a lot, all over the world. I have been to Spain at least 10 times, Italy and Poland. And I know Armenia better than those who live there,” he says.

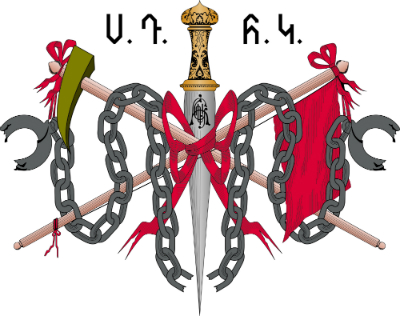

Yervant Balian was even engaged in politics at a time, especially in the ranks of the Social Democratic Hunchakian party … “I was shot on October 18, 1958 (during the political crisis and the armed clashes that took place in Lebanon at the time), he said showing bullet marks on his chest … I even worked as a bodyguard for some great political figures. But today, it’s over. “My policy is my family,” he assures, without giving a name. The page is turned.

Like many Lebanese, Yervant saw his three children emigrate one by one after their studies and none of them ever expressed the wish to take over his business. “My brother-in-law works with me now, but the industrial sector is in decline all over the country. No one wants to do this job. It is expensive to buy the machines and models from which we work. Moreover, Lebanon is in a state of chaos. There is nothing more that works in this country,” he laments.

This article was originally featured on https://www.lorientlejour.com and translated from French by MassisPost staff.