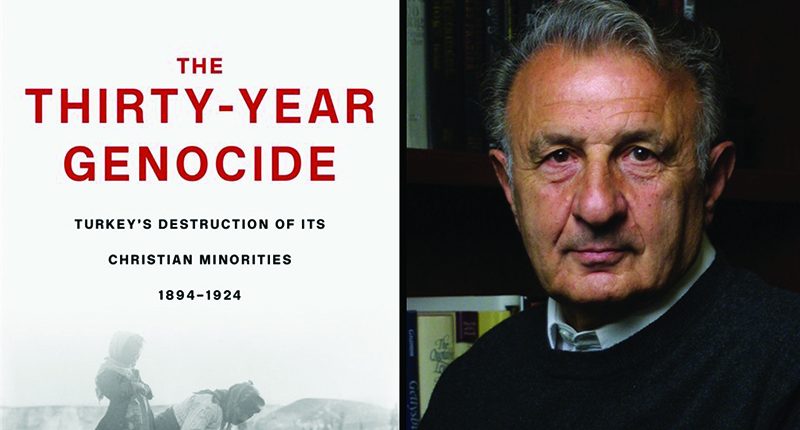

The Thirty-Year Genocide, Turkey’s Destruction of its Christian Minorities 1894-1924

By Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi. 656 pages, Harvard University Press

Published April 24, 2019

A Non-Review by Gilbert Bilezikian, Th.D., Professor Emeritus, Wheaton College

We Armenians have reached a point in the history of our nation when the survivors of our Genocide, our parents and grandparents, have left us for their eternal destiny, taking with them their sufferings, their sorrows and their secrets. We, their children, have often deplored the conspiracy of silence which, for whatever reasons, caused them to conceal from us the atrocities they had witnessed and suffered during the Armenian Genocide.

I must confess here how I cheated on my parents to learn what I had never been intended to know. The following excerpt from another book conveniently relates the story:

“Little boys are supposed to sleep soundly. I never did and, as an old man, I still don’t. The only place available to go to bed in the tiny apartment of the Montmartre neighborhood in Paris where our small family lived was the sofa in the front room. My parents were survivors of the Genocide inflicted upon the Armenian religious-ethnic minority while the world was busy doing war during the early part of the last century. World War I had become the occasion for the first occurrence of ethnic cleansing in modern times as it was perpetrated with consummate efficiency while the Western nations were busy destroying each other. A million and a half Armenian Christians were systematically massacred while the rest of the population managed to flee their bloodied Homeland. My parents escaped the carnage and made it to Paris where I was born and raised.

One of my earliest memories has me trying to conceal under my blanket the fact that I was awake when my parents and their guests thought that I was safely asleep. They met around the table, under a hanging bulb that cast a weird orange light reflected from the lampshade above it. They gathered periodically and, unaware that I could hear them, they whispered among themselves the horrifying stories of the depredations they had suffered during the Genocide as families, towns and villages. When they were all gone, I kept staring in the dark, eyes wide open, teeth chattering, tight little body, shaking irresistibly, deep into the night.

It is a documented fact that the survivors of the Armenian Genocide, now practically extinct, have not spoken to their children about it. Their silence has been explained as an attempt to spare their progeny the trauma they themselves experienced, or as their inability to come to terms with the magnitude of the devastation they suffered. But they spoke about it freely among themselves, as if attempting to glean from each other an understanding of what happened to them.

Frozen with terror, I strained to hear every word they spoke. While simulating sleep, I clenched my teeth on my blanket to prevent them from chattering and thus betraying my awareness. I remember hearing sobbing accounts about fathers being tortured to death in front of their families, of women and children forced out by the ten thousands on one-way death marches into the Syrian desert of Der-Zor, of churches set on fire with hundreds of refuge-seeking innocents trapped inside, of my maternal grandfather Garabed Kupelian, a beloved pastor, killed with eighteen Christian leaders on their way to a church convention in the city of Adana.”

(How I Changed my Mind about Women in Leadership by Bilezikian in Alan Johnson ed. pp. 50-51)

And now, decades later, this newly published book makes a thunderous landing on my desk. Hardly cracked open, it forces me to re-examine my understanding of the Armenian Genocide. Instead of the formal academic book review I was assigned to turn in, here are a few observations thrown together which I hope will motivate readers to grapple themselves with the story.

The Thirty-Year Genocide was written by a team of two Jewish professors at the Ben Gurion University in Israel for the purpose of transforming “how we see one of modern history’s most horrific events.” At first thought, the available Armenian Genocide literature is so extensive that it does not seem that much can be added to its understanding. However, the reader quickly discovers that the thoroughness and the minute attention given to the research challenges traditional insights and breaks new ground in several areas of Genocide theory. It is generally agreed that the designation “Armenian Genocide” refers to the campaign of spasmodic destructive frenzy that caused the Ottoman government to decimate the Armenian population that had occupied the land of Anatolia long before the Turkish hordes from central Asia had invaded it during the eleventh century. This book makes a persuasive case for the proposition that the Genocide was not primarily a systematic program of ethnic cleansing aimed at eliminating the Armenian population in one massive strike under the rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid. More accurately, it unfolded in three stages that led to the horrors of extermination inspired by the anti-Christian jihadic expressions of religious fanaticism that found their fulfillment in the policies of Mustafa Kemal. The book chronicles the evidence that the Armenians in Turkey suffered a protracted agony of extinction that stretched over three decades which culminated with the ascent to power of the founder of the Turkish Republic.

By cleverly exploiting the disarray of his country’s government, Kemal, the victor of the battle of Gallipoli, was able to exploit to his own advantage the turmoil of his time to secure a position of dominant military and political power. I remember sitting in class during the 1940s in my Parisian public school where he was depicted with reverence as the iconic revolutionary hero who delivered the Turks from the colonial ambitions of the Great Powers to lead his people from backward medieval conditions into the magic and the wonders of the modern world. Again, this book comes to our help by providing the elements of a realistic profile for Kemal that depict him as a somber, calculating, perfidious opportunist who manipulated the jihad option to bring the thirty-year Genocide to a climactic conclusion that was extended to include the Christian Greek and Assyrian minorities, and that surpassed in cruelty and savagery what had already been inflicted on the Armenians.

The existence of the Armenian Missionary Association of America bears witness to the emergence of a missionary movement among churches and denominations a century or more ago. Once the task of nation-building had been achieved in the Western countries, the eyes of Christians, especially Protestants, turned beyond their home-shores toward the spiritual, educational and medical needs of peoples on all continents that were devoid of the Christian message. As a result, missionaries from America and Europe were already present and active in Turkey when the Armenian massacres began in 1894. The authors of our book have taken time to describe and carefully reference scores of stories of interventions by dedicated Christian foreigners who reached out to harassed Armenians as protectors, intercessors, conciliators, providers, rescuers, first-responders, caregivers, doctors, nurses, guardians of orphans, chroniclers and gravediggers. This witness to the self-sacrificing dedication of the apostles of mercy gains credibility in consideration of the fact that it is borne in this book by two objective non-Armenian and non-Christian distinguished Jewish scholars. As a matter of fact, some of the readers who are holding this book in their hands at this instant, whether they know it or not, owe their existence to the altruism of those heroes who have now passed away in anonymous obscurity—many of them buried in nameless graves in the faraway land where they served. The authors of the book are to be congratulated for this tribute to the missionaries, carriers of mercy caught in a monstrous nightmare of rampaging inhumanity.

But primarily, the authors are to be congratulated for the inception and, after many years of meticulous research and writing, for the publishing of this book. It will stand in both the historical records of nations and in the field of Genocide studies as a monumental marker of excellence. The incentive for the commitment to this task could have naturally devolved from the chronology between the Armenian Genocide and the Jewish Holocaust. Indeed, the spacing in time of the two events calls for the comparative study of historical contexts and causality which is available in the book. But there may be more to it. It is well known that a number of Israeli intellectuals view the present policies of their government critically, as if calculated to build a capital of hatred so intense that it may not be containable through diplomacy. Like the Armenians were in Turkey, they realize that they constitute a tiny religious and ethnic minority surrounded by Muslim nations committed to their annihilation. They consider that their leaders’ policies of colonization through territorial expansion and military oppression do not bode well for the future of their country. They also realize that their reliance on American power and nuclear weapons would not withstand the attack by the dozen surrounding, equally armed nations, numbering half a billion Muslims tightly gathered together, three circles deep, as a formidable siege fortress with little Israel in the middle. Although its authors do not touch on this notion, it may well be that their book could serve as a cautionary warning to alert their people to the dangers that loom ahead.

Finally, the words at the end of the book may be the most important. Astoundingly, there is no discussion in the book about the multitude of Genocides that have occurred across the planet since the Armenian Genocide and the Jewish Holocaust. No suggestions are made for possible recourse to international agencies to adjudicate conflicts that become genocidal, for the recourse to sanctions and boycotts, and for the intervention of peace alliances. In particular, no instructions to bring to reason those guilty of Genocide except for confrontation with facts in the face of denials and cover-ups, in the hope that the truth can prevail and bring restoration to honor and to good-will in the family of nations. The dispirited mood reflected in this fish-tail ending of the book may find explanation in the last five words of the concluding sentence of the whole volume:

“We hope that this study illuminates what happened in Asia Minor in 1894-1924, that it will generate debate and, in Turkey, reconsideration of the past.”