By Dr. Hratch Tchilingirian

On the 75th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, in a joint Communiqué issued on April 29, 1989 for the occasion, Their Holiness Vazken I Catholicos of All Armenians and Karekin II Catholicos of Cilicia “propose[d] that the preparatory activities continue for the canonisation of [the Genocide] victims.” Indeed, the idea of religious commemoration of the Genocide victims goes back to the early years of the First Republic of Armenia (1918-1920), when the Armenian Government at the time formally applied to Catholicos Gevorg V to include the martyrs in the liturgical calendar of the Armenian Church.

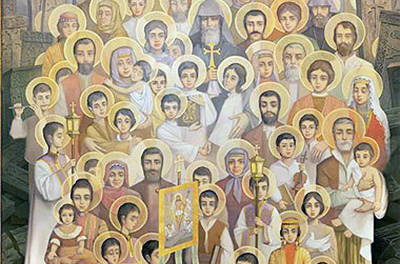

In November 2014, the Synod of Bishops, headed by the two Catholicoi of the Armenian Church, announced that the martyrs of the Genocide will be formally declared saints on 23 April 2015. The solemn ceremony took place in Holy Etchmiadzin on the centenary of the Genocide, where the newest saints of the Armenian Church were announced and venerated.

Canonisation is the final stage of declaration of sainthood—the last one in the Armenian Church was done some five hundred years ago—whereby a person or a group of persons are considered to share the holiness of God and their lives bear witness to the authenticity and truth of the Christian gospel. Saints are believed to have joined God in an endless sharing of a divine life beyond all corruption and have found the true life with God. As such, with their exemplary lives, the saints are an integral part of Christianity since ancient times and have a significant place in the doctrinal, liturgical and pietistic traditions of the “One, Universal, Apostolic, Holy Church”.

In the last three decades, the discussions of the canonisation of the Armenian Genocide victims were confined to various committees and a narrow circle of clergymen. The deep theological meaning of sainthood and its relevance to faith and piety have hardly been explained to the ordinary Armenian faithful. The saints are canonized primarily for the faithful. Declaring the Genocide martyrs as saints is not rewarding them the “medal of honour,” but to provide role models to emulate and to continue the evangelistic and spiritual mission of the Armenian Church in Armenia and the Diaspora.

Were the victims of the Genocide canonized by the Church for its “symbolic value” on the 100th anniversary of the Genocide or will the declaration of these new saints provide a unique opportunity to renew and revitalize the Armenian Apostolic Church in the 21st century? This is an important question that needs serious discernment.

Theological and Political issues

Theologically, now that the victims of the Genocide have been canonized, the Armenian Church is under a dogmatic imperative, that is, they are no longer victims, but victors of Christ. Now that the victims of the Genocide are canonized, we can no longer hold Hokehankists (requiem services) to mourn their death, to which we have accustomed ourselves. Instead, we will celebrate the Divine Liturgy invoking their names, asking for their intercession and celebrate their victory over death, in and through Christ. The mournful, dark atmosphere of commemorations of the Genocide will have to be changed into a “festive” atmosphere. The victims are no longer victims, but saints who live in the glory of God, that is, those who have joined God in an endless sharing of a divine life beyond all corruption and have found the true life with God. Hence, the question is whether Armenians are willing to see themselves as witness to the Death and Resurrection of Christ—for whom hundreds of thousands of Armenians gave their lives—rather than perpetually identify themselves as the victim.

Politically, ever since the 50th anniversary of the Genocide, Armenians have been collectively demanding justice for the 1.5 million victims of the Genocide from Turkey in particular and the world in general. While canonising the victims de facto resolves the problem of justice for their lives, the political demand for justice on behalf of saints of the church remain a problematic issue. Furthermore, the territorial question with Turkey might also be complicated. As it is customary with saints, does it mean that the places where Armenians were martyred would be considered shrines or Armenian “holy lands”? Still, there are many indirect political implications which need to be carefully examined.

The recent canonisation of the Martyrs of the Armenian Genocide should not be viewed as an event that added “glitter” to the observance of the 100th anniversary of the Genocide. Even as Turkey and many countries around the world continue to deny the fact of the Genocide, canonisation should not be viewed as a response to denial and, in our frustration, as a gesture of bestowing the ultimate honour to our victims by declaring them saints. We would do injustice to the victims without recognising their martyrdom for Christ and its impact on our lives individually and on our nation collectively. The saints in the church are—like celebrities today in the secular world—figures of admiration and models to emulate. Armenian Christians are called to discern the saints’ virtues and follow their example in obtaining the “heavenly crown of glory”. Canonising the martyrs of the Genocide is to perpetuate their witness to Christ through the Armenian Church’s mission and evangelism in this world.

(Hratch Tchilingirian is a scholar at University of Oxford, www.hratch.info)