By Lucine Kasbarian

BELMONT, MA — He documented monumental, now-vanished Armenian architecture. He painted representations of our women in folkloric dress. His reproductions launched public awareness of Armenian manuscript illumination. He illustrated the creativity of Armenian ornamental inscription and sculpture. And he designed the currency and postage stamps of the First Republic of Armenia in a way that celebrated our artistry and traditions. The man was Arshag Fetvadjian (1866-1947), and through the meticulous research of eminent Armenian art historian Levon Chookaszian, the global Armenian community and art lovers alike have been given the opportunity to rediscover a true son of the Armenian nation whose love of homeland highlighted nearly all of his accomplishments as a leading Armenian artist and art historian of the 19th century.

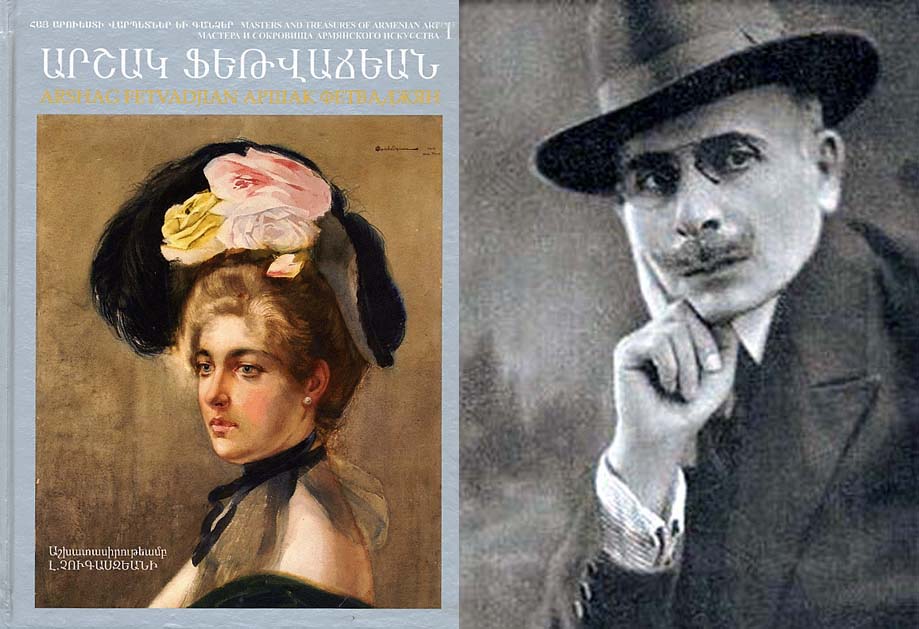

Chookaszian, founder and director of the UNESCO Chair of Armenian Art History at Yerevan State University, has embarked on a lecture tour to celebrate Fetvadjian and the release of Chookaszian’s book about the art legend. (“Arshag Fetvadjian,” in English, Armenian and Russian, $75, Yerevan, Armenia: Printinfo, 2011.) In an intimate, engaging and inspiring multi-media lecture, Chookaszian did justice to the many facets of Fetvadjian the man and the diversity of his artistic aptitudes.

This event was held on Nov. 7 at the National Association of Armenian Studies and Research’s (NAASR) in conjunction with an exhibition of Fetvadjian’s work at the Armenian Library and Museum of America (ALMA), a co-sponsor of this event.

Born in the Black Sea region of Trebizond, Fetvadjian, at age 16, enrolled at the Imperial School of Fine Arts in Constantinople. Graduating with high honors, he was awarded the school’s “Rome Prize,” which would allow him to study in Italy with the proviso that he return to Turkey and accept a state position. As Chookaszian explained, Fetvadjian turned down this prize on the recommendation of a trusted advisor, Voskan Bey Mardikian.

Under the veil of anonymity, Mardikian bequeathed a sum for Fetvadjian to pursue his art studies in Rome but advised him to never return to Turkey. Instead, he urged Fetvadjian to go forth into the world and promote the unsung greatness of a beleaguered Armenia through his art.

While in Italy, Fetvadjian “became inspired by the heroic spirit of the Italians who were freed from Austrian control,” wrote Chookaszian in his book. “That inspiration was essential for the formation of artistic and political views of Fetvadjian.”

As was evident from the body of work he left behind, Fetvadjian was an ardent defender of “hayabahbanoum,” or preservation of the Armenian identity. “It was as if a voice from within was telling him to mark out our national treasures on the ground,” said Chookaszian. And this was with good reason, he continued, “as many if not most treasures did not withstand the depredations of the Genocide, nor was the Western world aware of them.”

Fetvadjian’s many illustrious colleagues included the father of Armenian architectural historiography, Toros Toramanian, with whom Fetvadjian studied the remains of medieval Armenian architectural monuments, particularly at Ani, the famed Armenian city of 1,001 churches. Among Fetvadjian’s best-known paintings is “Woman of Sassoun,” a rifle-clad matron defending the Armenian highlands from the Turkish onslaughts while suckling a child said to metaphorically represent Armenia. Many elder Armenian-Americans will recall when Fetvadjian was commissioned to create his magnificent painting of a very Armenian-looking “Madonna and Child” that still graces the altar of St. Illuminator’s Armenian Cathedral in NYC. All in all, Chookaszian’s presentation made abundantly clear that Fetvadjian is to be venerated for documenting and popularizing many aspects of our ancient culture and customs through his works.

Even though Fetvadjian has been honored with two large exhibitions in Yerevan, in the 1950s he was all but forgotten by the Soviet Armenian authorities, and by extension, the natives of the land. Fetvadjian was undoubtedly neglected in the Soviet era because of the patriotic nature of his work and his close association with the first Republic of Armenia. Had Fetvadjian’s works been made available during Soviet times, asserted Chookaszian, his paintings, research, reviews and documentation would have been able to influence and inform generations of multi-disciplinary scholars, artists and others, not only in Armenia but the world over.

After studying and creating art around the world, Fetvadjian came to NYC to pursue his profession while living under spartan conditions. Weary, depressed and longing for his native land, he was urged by Manuel Der Manuelian, one of the four consuls of the first Republic of Armenia, to immigrate to Boston, where he lived for the last 25 years of his life. Manuel’s offspring, Vigen, Haig and Lucy Der Manuelian, were all deeply affected by Fetvadjian’s presence as an adoptive member of their family. This is greatly evidenced by the accomplishments of all three children: Vigen and Haig pledged to open a museum as a tribute to all that they had come to love about Armenia and its people, resulting in their establishment of ALMA. And Lucy became a prominent historian of Armenian art and architecture in her own right.

Just as the government of Soviet Armenia in 1947 extended an invitation for Fetvadjian to return and live in Armenia, he passed away in Massachusetts, but not before packing up his life’s work to bequeath to the National Gallery of Armenia for safeguarding and exposition. It was Levon Chookaszian’s grandfather’s cousin, Barkev Chookaszian, who led the drive to return Fetvadjian’s art, archive and human remains to Armenia.

While master artists such as Vartkes Sureniants and Krikor Khanjian are roundly celebrated for capturing the imagination and reverence of the Armenian people, we have visionary art historians such as Chookaszian to thank for reinstalling Fetvadjian into our collective memory and into the very same pantheon of illustrious Armenian national artists.

Among their many other accomplishments, Levon Chookaszian and his brother Karekin are to be thanked for initiating the Virtual Museum of Armenian Art, a multimedia software series created to safeguard and promote the endangered world of our Armenian art heritage.

The lavishly illustrated “Arshag Fetvadjian” book is available at NAASR Bookstore in Belmont; Abril, Sardarabad and Berge Bookstores in Los Angeles; and Artbridge, Noyan Tapan, and Matenadaran Bookstores in Yerevan, among others.