BY KADIR AKIN

Remarks made by Vehbi Koç, the prominent businessperson of Turkey years ago, regarding the military service law applied to non-Muslims gained renewed attention on social media as the number of soldiers who lost their lives in cross-border operations reached 21 within three weeks, and a majority of these soldiers were from economically disadvantaged families. What did Vehbi Koç say in his statement?

“The Turks used to go to the military to die or get sick. Catholics, Armenians, and Jews paid a price and didn’t serve in the military. They earned big money and lived in the most beautiful places. We used to admire them from afar.”

These words highlighting the exemption of the wealthy’s children from military service through the paid military service law and drawing attention to the fact that the soldiers who lost their lives were mostly from poor families became a useful argument for those unaware of the practices of that time. Were non-Muslims not going to the military because they were wealthy, or were they not being drafted at all? Were “Catholics, Armenians, and Jews” always rich, while Turks (actually Muslims) were always poor? Was Vehbi Koç, born in 1901, recounting what he heard, or was he sharing his own observations?

Those unaware of the debates and who advocated for what in 1911, during the discussions in the Ottoman Parliament (Meclis-i Mebusan) on this issue, immediately relied on memorized narratives. These words were enough to fuel chauvinism and racism, of course.

The “socialist deputies group”

After the proclamation of the Constitutional Monarchy and the re-enactment of the Constitution (Kanun-i Esasi) following the 1908 revolution, the Parliament was reopened, and parliamentary work began with two-tiered elections. In the parliament, there were a total of 288 members, including 147 Turks, 60 Arabs, 27 Albanians, 26 Greeks, 14 Armenians, 10 Slavs, and 4 Jews. In the writing of history, all Muslim deputies were considered Turkish, so those who came from the Kurdistan provinces were not specifically mentioned. This situation in the Meclis-i Mebusan indicated the success of both Abdulhamid’s and the Unionists’ policy of considering Kurds as “one of them.”

In the reopened Parliament, two representatives from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) on the Union and Progress Society’s list, one from the Thessaloniki Socialist Workers’ Federation (SSIF), and one from the Social Democrat Hunchak Party (SDHP) started to actively work in the Meclis as a “workers’ rights protection group” or “socialist deputies” group. It is highly beneficial to revisit the words of these four deputies during the sessions where the military service law was reorganized and discussed in the Ottoman Empire. It is valuable to review these statements especially for the leftist/socialist movement to confront its lack of political history consciousness.

These four socialist deputies engaged in discussions on education, justice, women’s rights, tax inequality, unions, and freedom of organization. Additionally, they participated in debates about conscription and the position of non-Muslims within the military.

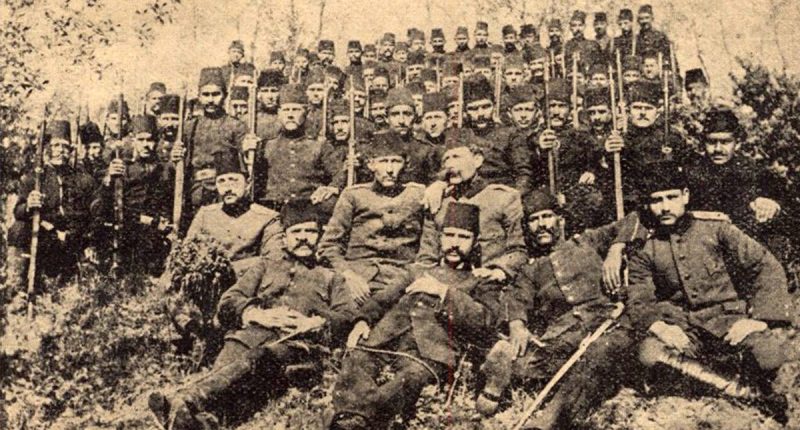

In 1895, non-Muslims began to be included in gendarmerie regiments; however, these attempts were not successful due to the challenging conditions imposed on non-Muslims and their resulting reluctance. In 1909, a bill was introduced to the Parliament, and after various discussions and debates, it was accepted in July 1909. Armenian deputies were supporters of the prompt enactment of the law conscripting Christians. They believed in the Ottomanist program of 1908 and thought that this inequality needed to be eliminated. On the other hand, the ruling members of the Committee of Union and Progress (Ittihat ve Terakki) were inclined to continue exempting Christians from military service in exchange for a fee, seeing it as a significant contribution to the state budget.

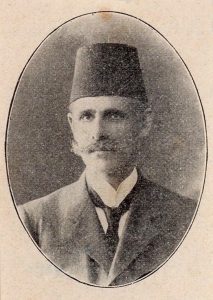

In fact, this situation favoring wealthy Christians was detrimental to the poor Christian population and peasants. Those who couldn’t afford the requested amount found themselves in an illegal situation. Regarding this issue, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (EDF) organized a comprehensive discussion about the conscription method, procedure, and timing in a public meeting in Istanbul’s Beyoglu. However, SDHP representative and Adana deputy Hampartsoum Boyadjian were proposing certain methods and procedures. Due to his long imprisonment and years in exile, Boyadjian was familiar with the structure of the Ottoman Army. He suggested the “militia” proposal and cited the example of Switzerland. Undoubtedly, this topic was one of the most sensitive issues for Turkish deputies. The concept of militia, instead of a regular army, was not easily understood by them. In response to the strong objections to this proposal, Boyadjian would say:

“So, I am not claiming that we can teach in six or seven weeks, three months. No, I am claiming from a different perspective; let it be six months instead of three months. Today, we all agreed that teachers should be exempt, and one of those teachers is me. But if today we had a sufficient number of teachers to meet the need, I would argue that even teachers should be soldiers. I have another consideration. If our armies had educated, cultured, well-mannered, duty-conscious, exempted teachers in sufficient quantity in contact with the troops, including teachers like me, it would have significant spiritual benefits, there is no doubt about it. If it were like that, we would have been immune to incidents like the March 31 events*. Therefore, I wish that educated individuals have contact with our soldiers. Because, as I said, it has a spiritual benefit. If we were to think from the standpoint of equality, there is no doubt that if we had adopted the militia system in the military, today the entire nation would have learned military duty.”

“The poor will always die, and the rich will always win”

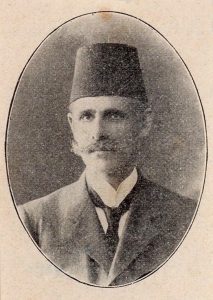

Vartkes Serengülyan, who was elected to the Parliament with a hundred thousand votes from Erzurum, emphasized the injustice and unfairness of only children from poor and destitute families being enlisted, advocating for the inclusion of everyone in military service regardless of class distinctions. Amidst the usual criticisms and protests against his socialist personality, he continued his speech, also demanding higher fees for those who avoided military service by paying.

“Therefore, if the ideas I present are contrary to Christianity or our Civil Law, reject them. Rejecting my genuine words by simply saying ‘he is a socialist’ is not a success. And I believe that it is not conducive to the interests of the nation. As you understood, going a bit towards socialism is necessary. Now, it is our right to benefit excessively from the rich… I mean, the poor will always die, perish, and the rich will always win. You cannot deny this. They are paying 50 lira and getting away with it.”

“Vartkes (Continued) – They pay 50 lira and get away with it. Thanks to their wealth, they don’t send their children to the battlefield. They are deprived of the honor of being martyred in battle! Since such things are a great honor! Since aiding the poor is the duty of the rich, I say there should be a proportion. As Cavit Bey said, those with income up to 2000 should contribute 12%. Those up to 5000 should contribute 15%. Those up to 10000 should contribute 20%. Even if someone with a million income gives 100,000 lira a year, what harm would it do? Gentlemen, know well that if our soldiers’ barracks do not have the ignorant, the learned, the poor, and the rich sitting together, there will never be success. It is necessary for the children of the learned, the rich, and the poor to sit together. Then they will understand that they are all equal, all children of the same homeland, all members of the same family. Otherwise, when I receive the news of my child’s death in battle while I see the child of an educated or wealthy man walking in front of me, instead of feelings of equality and brotherhood, I will feel hatred and enmity. It is such a truth that a person should not have logical reasoning not to say it openly. Mustafa Arif Bey says, since the children of the rich can get rid of this duty by paying a fee and serving for three months, why shouldn’t the learned also be exempted from this service for three months. He is absolutely right. This is truly an unfair treatment. But it is not right to commit another injustice for this injustice. I am against this.”

In the same session, Boyadjian would also object to the preservation of the “Hamidiye Regiments” by changing their name to “Light Cavalry Regiments” in the legislation.

Undoubtedly, the socialist Armenian deputies must have faced significant challenges while debating this law. On one hand, they tried to advocate for a just conscription system considering the conditions of that time, and on the other hand, being familiar with the functioning of the Ottoman military system, they could anticipate the difficulties that non-Muslims would face. However, historical events would later reveal that in 1909, the implementation of conscripting non-Muslims would lead to the systematic and mass killing of tens of thousands of Armenian youth in the “labor battalions” where they were employed for road construction and maintenance in 1915.

In 1915, as defenseless convoys from the Anatolian interior were driven towards Deir ez-Zor, the majority of these convoys consisted of the elderly, women, and children. After being uprooted and forced onto this journey of death, those who seized their remaining possessions and property had the audacity to say, ‘…they didn’t serve in the military. They made big money and lived in the most beautiful places. We used to admire them.’ This statement is not only tactless but believing in it is sheer ignorance.

*The 31 March incident was a political crisis within the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. Occurring soon after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, in which the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) had successfully restored the Constitution and ended the absolute rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (r. 1876–1909), it is sometimes referred to as an attempted countercoup or counterrevolution. It consisted of a general uprising against the CUP within Istanbul, largely led by reactionary groups, particularly Islamists opposed to the secularising influence of the CUP and supporters of absolutism, although liberal opponents of the CUP within the Liberty Party also played a lesser role. The crisis ended after eleven days, when troops loyal to the CUP restored order in Istanbul and deposed Abdul Hamid. (Source: Wikipedia)

Bibliography:

Kadir Akin, Sakli Tarihin Izinde (In the Traces of Hidden History), Dipnot Yayinlari, 2nd Edition, 2021, Ankara, pp. 313-316

Yegig Cerecyan, Medzn Murad-Hampartsum Boyaciyan, Institute of History, 2006, Yerevan, p. 131

Turkish Grand National Assembly (TBMM) Archives, October 17, 1911, Vol. 1, p. 183

Turkish Grand National Assembly (TBMM) Archives, October 17, 1911, Vol. 1, p. 175

(KA/VC/PE)

https://bianet.org/