Dr. Mary A. Papazian, newly appointed President of Southern Connecticut State University, wrote the following review in Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies, Volume 19:2, which is here reprinted with the permission of the editors.

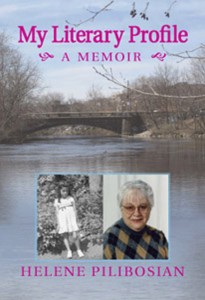

In ‘My Literary Profile: A Memoir’, Helene Pilibosian, long-time editor of The Armenian Mirror-Spectator, has written a personal and intimate memoir in which she charts her own literary development over the course of a full and active lifetime. Some of what she tells will be familiar to her readers; other details of her personal experiences and development will surprise all but her closest friends.

The daughter of genocide survivors and of the first generation born in America, Pilibosian looks back on her life growing up in Watertown, Massachusetts. Coming of age in the middle of the last century, she expresses multiple threads of influence, from the emerging Armenian community in Watertown to her experiences as a student in the Harvard Extension School, her mature years as a wife and mother, and finally to her evolution in her later years as a writer and poet who is constantly seeking her voice, which is another word for her own self-identity. Pilibosian’s “literary memoir,” which she publishes through a micro-press, Ohan Press, that she established with her husband Hagop, is the story of her life, and in it her attempt to understand the influences that led to her growing identification as a poet and writer. This story of self-discovery and growth is clear, direct and honest. . . and it is a story that reminds us that we need never stop learning and developing.

Narrating her story more or less chronologically, Pilibosian begins with her early years as “the second daughter of Khachadoor or Archie and Yeghsa or Elizabeth Pilibosian” (p. 1). In the very way she represents her parents through their dual Armenian and American names, Pilibosian underscores her own duality as a representative of the first generation of hyphenated Armenian-Americans growing up under the influence of the stories of the generation of genocide survivors. Her efforts to understand and interpret this duality underlie the entire narrative, as do her efforts to place her experiences within the American cultural development of the twentieth century. The tension between the two strands is more acute in the years before her long and seemingly fulfilling marriage to Hagop Sarkissian, an immigrant from the vibrant Armenian community in Beirut, Lebanon, who enabled Helene to bridge the gap between her two worlds.

Pilibosian’s early years were typical of that of many immigrant Armenians—and indeed many immigrant Americans from many other cultures and countries—in the first half of the twentieth century. And thus in its particulars, her memoir exudes a kind of universality. She tells the story of her father’s survival during the Armenian Genocide, where “On the death march he had been taken from his mother, his brother and his two sisters by a Kurd who sold him to another Kurd for a goat” (p. 4). He escaped this captivity four years later and fled to an orphanage in Aleppo, Syria. Ultimately, he came to America, joining his father in Whitinsville, Massachusetts, and set out to make a life for himself. An important step in establishing himself in the new world was his marriage following a “courtship by mail” to Yeghsa Haboian, a young Armenian woman who had settled in Gardannes, France.

Although she spends some time telling her parents’ moving stories of survival and renewal, Pilibosian’s story is not primarily a story of the Armenian Genocide, nor of the experiences of those who would survive the tragedy. In fact, while the book contributes to the growing body of survivor literature, it is primarily the story of the next generation. She, a child of survivors, provides the details of the genocide to lay the foundation to explain her own experiences and those of other members of the next generation and the communities they built. In this way, this essay more aptly shares in the tradition of Peter Balakian’s Black Dog of Fate (1997), among others.

While many figures wander in and out of the narrative . . . from friends and family members, to teachers, professors, and even intellectual figures whom Pilibosian came to know not in person but through their writings, the story really is about Pilibosian herself. The many quotations from authors, artists, writers, teachers and thinkers, such as Arshile Gorky, Professor Howard Mumford Jones, the poet Paul Engle, that she presents provide a taste of those who influenced her intellectual and artistic life. Pilibosian came to know many of these individuals while she was a student studying humanities at the Harvard Extension School. Others were leading Armenian intellectual figures whom she met while traveling with her husband to his native Lebanon or in Europe to visit family members and fellow Armenians. Still others were caregivers, psychologists, and physicians who supported her through a nervous breakdown in her twenties and through other health issues later in her life.

In writing this memoir, Pilibosian bares her deepest secrets. She tells the story of her struggles with depression, as well as the shock treatments she underwent, her weeks in hospitals under the care of a psychiatrist, her cardiac arrest and near death, with honesty and forthrightness. These are stories that many would want to keep hidden, and, I would bet, many of her Armenian readers never knew of them. Yet Pilibosian sees them as critical to her intellectual and emotional development as a person and a poet. And thus she shares them in an honest, direct, and unapologetic style. These things happened to her—and thus they shaped her.

What strikes the reader throughout the narrative is the love and support Pilibosian received throughout her life—especially from her husband—that enabled her to overcome these challenges and lead a productive and prosperous life, one in which she never ceased exploring the world of ideas and emotions, and one in which she never stopped giving. While this memoir is clearly her story, it is in no way self-centered or narcissistic. Rather, it strikes this reader as an honest attempt at self-understanding, and one that she hopes will provide strength, comfort, and encouragement to those who read her work . . . whether in the form of this personal narrative or through her several volumes of poetry. It is, ultimately, a story of survival and healing made possible by love and the transformative quality of poetry.

(Ohan Press website http://home.comcast.net/~hsarkiss, contact Helene Pilibosian at [email protected])