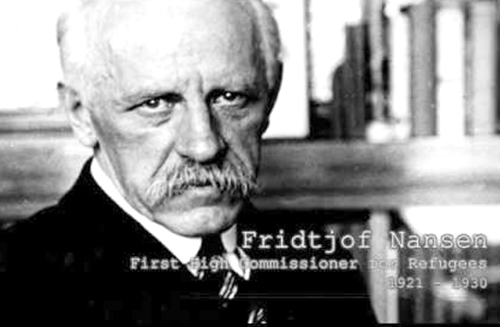

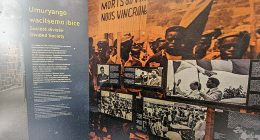

I watch the powerful images of hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing war in the Middle East and I hear the harsh voices of some senior government officials and state bureaucrats claiming that little can be done since these “people on the move” lack proper government identification. However, I also recall the illustrious Norwegian diplomat Fridtjof Nansen and his innovative and creative solution to a similar bottleneck in the humanitarian crisis that affected the Middle East and Europe almost a hundred years ago.

Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930) was a Norwegian scientist, polar explorer, diplomat, human rights and refugee official and Nobel Peace Prize recipient (1922). Achieving international fame first as an artic explorer, oceanic scientist, and author, Nansen became active in national and international diplomatic service. He served in Norwegian Foreign Service postings in London and Washington.

During WW I, Norway remained neutral while most of Europe was at war. This previous neutrality became useful in the difficult post-WW I era when empires fractured, ethno-political boundaries were redrawn, and vulnerable newly independent states emerged. From 1920 onwards, Nansen worked with the League of Nations and in 1921 Nansen was appointed the first High Commissioner of Refugees. During the protracted peace negotiations, a great many persons were still prisoners of war (e.g. German and Russian) or stateless refugees/deportees, often without adequate identity documentation. This meant that that it was exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to cross borders to safer destinations. To solve this administrative bottleneck amidst an ongoing humanitarian crisis, he proposed the “Nansen Passport”. It was, in essence, an international document that identified an individual sufficiently to allow that person to travel freely across borders to eventual sanctuary. As a result of the Armenian Genocide, hundreds of thousands Armenian refugees and orphans existed throughout the Middle East. A large number of Armenians opted to use a Nansen Passport to travel to a safer country. Even larger number of other refugees used such “passports” to reach safety.

Nansen had also become involved in the somewhat controversial, but urgent, Greek-Turkish compulsory exchange of populations following the Greek-Turkish war of 1922. In this exchange, approximately 1,250,000 Greeks were sent from Turkey, while about 500,000 Turks were sent from Greece. He also assisted in famine relief in Russia and Ukraine. In recognition of his tireless humanitarian work, Nansen received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1922.

Nansen died in May 1930. The League of Nations and later the United Nations honored this pioneer of humanitarian assistance to post-war refugees. This remains an urgent issue that still challenges the global community. On the 150th anniversary of his birth, the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute issued a medal in 2011 in honor of Fridtjof Nansen and his humanitarian work. He showed that one person’s humanitarianism can make a difference, but it also requires much more effort by others. The events of the past few weeks remind us of this.

This article is a condensed and slightly modified version of the entry on “Fridtjof Nansen” appearing in Alan Whitehorn, editor, The Armenian Genocide: The Essential Reference Guide (ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara, 2015).