The CMHR’s website displays a letter to the Globe & Mail, dated March 23, 2011, in which CMHR officials state that “The Canadian Museum for Human Rights is not a museum of genocide, it never was. It is a catalyst for change. The Museum is … not a memorial to the past.” The sentiment is echoed by the museum’s CEO during his interview in the article. This adds a whole new set of issues to the existing controversy over the absence of an inclusive and comparative approach to cases of genocide.

The Holocaust, to which the CMHR is devoting an entire gallery, is most definitely a genocide. Indeed, it is a prime example of genocide and should be a central part of the museum. Genocide is not a matter of the past: even those genocides that occurred many years ago continue to have major effects. Just as one can not teach about human rights without taking genocide into account, so one can not teach about genocide without taking the Holocaust into account, but through a comparative approach with other cases of genocide.

The claim that “it never was” about genocide is surprising, given that the CMHR has issued press releases and promotional material in which genocide figures prominently. One press release, for example, titled, “20th Century Genocides,” has on its first page the heading, “Stories of the 20th Century Genocides—The Vision,” where one reads:

“Prejudice, racism, grievance, intolerance, aggression, injustice, oppression—they all start small, and we need to spot and stop them in our own local orbits before they grow and get out of control. This means looking at the often long prehistory of genocide, as well as its symptoms in the present. Understanding these will help avert future horrors.

“As the visitors to the Museum arrive on the third floor of the Museum, they enter a transition zone where an unfolding series of images, questions and quotes takes them onto a global stage and the dark side of the rights story—the denial of human rights that can result in genocide. The names of 20th century genocides—Armenia, the Ukrainian Famine, Nanking—appear with those of other crimes against humanity. The Armenian Genocide was the first genocide of the 20th century. This genocide, unpunished and denied, illustrated how crimes against humanity can escalate into genocide as seen in future genocides such as the Holocaust, Cambodia, Rwanda and Sudan.”

We agree. Only in this comparative way can one find general truths about the nature and mechanics of genocide as a general problem of humanity, which can help finding solutions to how genocide can be prevented.

The museum does not have to be a memorial to the past, but it must certainly take account of, represent and explain the history, ongoing development of, and challenges to human rights, if it hopes to inspire learning and become a place of change.

To do this, the Holocaust should be employed as a prime model of how to teach genocide. The Holocaust has been recognized by the world; its perpetrators have been tried and punished; the crime has been acknowledged by the perpetrator country; an apology has been extended, and reparations made. But it is critical to realize that other cases are necessary, as each provides its own particular lessons to be learned.

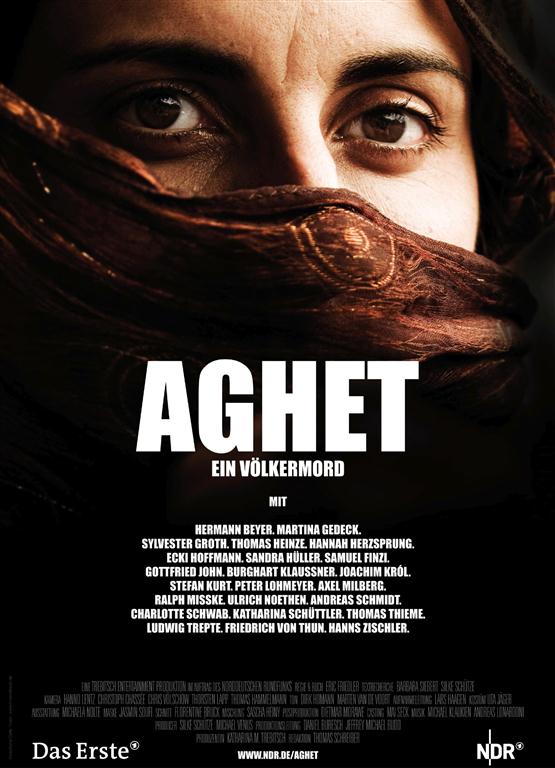

In the case of the Armenian Genocide, for example, the perpetrators mostly escaped punishment; the perpetrator country continues to deny that genocide took place and aggressively pressures others to participate in this denial. This is despite the fact that on May 24, 1915, the Allied Powers—France, Great Britain and Russia—declared that the Ottoman leaders would be called to account for their “crimes against humanity,” for the slaughter they were committing against their own Armenian citizens, whereby the term entered international jurisprudence.

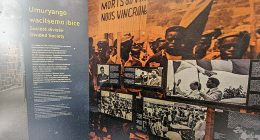

The Rwandan Genocide is yet another model. In this case, UN peacekeepers were in the country, and the head of the mission, Canadian General Roméo Dallaire, made every effort to warn the UN of the impending genocide, and the world via the news media, once it had started. Yet, the world powers made every effort to avoid calling it genocide, so as to evade the responsibilities of intervention. Each case has an important contribution to the understanding of genocide.

Taking these and the other cases of genocide into equal account would make all the various communities in Canada feel they are treated equitably, and that they are an important and integral part of the Canadian mosaic. It would help overcome the kind of thinking in cultural or ethnic “silos” that contradicts the objectives of Canada’s official policy of multiculturalism. In 1971, Canada was the first country to adopt multiculturalism as an official policy. The Act’s objectives are, in part, 1) to affirm the value, dignity and equality of all Canadian citizens regardless of ethnic origin, language, or religious affiliation; 2) to ensure that all citizens can preserve, enhance and share their cultural heritage, take pride in their ancestry, and still have a sense of being Canadian; 3) to encourage the accepting of diverse cultures and promote racial and ethnic harmony and cross-cultural understanding. One of the ways to foster these noble objectives, in the words of the Act, is to “encourage and assist the social, cultural, economic and political institutions of Canada to be both respectful and inclusive of Canada’s multicultural character.”

The CMHR is a national cultural institution, whose stated mission is, in part, to establish “a national and international destination—a centre of learning where Canadians and people from around the world can engage in discussion and commit to taking action against hate and oppression…. inspiring research, learning, contributing to the collective memory and sense of identity of all Canadians… to explore the subject of human rights, with special but not exclusive reference to Canada, in order to enhance the public’s understanding of human rights, to promote respect for others and to encourage reflection and dialogue.”

Taking a comprehensive and comparative approach to genocide as the ultimate violation of human rights would complement perfectly the objectives of Canada’s official policy of multiculturalism. It would avoid differentiating and dividing communities. It especially would make those communities who feel their histories have been neglected or denied feel more welcome. One can not overestimate the psychological trauma of those who are part of a nation that has experienced genocide.

Therefore, CMHR officials must recognize that genocide must be an integral part of the museum, as was envisioned and presented to Canadian society. This would facilitate the CMHR’s adhering to Canada’s policy of Multiculturalism, as well as its own mission statement, and make the museum a destination for everyone.

Read the article in Globe and Mail