DR. HRAYR JEBEJIAN*

I was born in Beirut, Lebanon, on February 8, 1957. I am a Lebanese-Armenian who has lived with dual identities and histories all my life – ones filled with struggle and wars, to say the least. The two unfortunately have several things in common, as you may tell: mainly the struggle to build life in the midst of uncertainties. Being born into a Christian family, topped with my Christian education at the Armenian Evangelical Church, very much shaped my career – which is to bring the Word of God to communities worldwide. I was lucky enough to be part of this mission with the Bible Society, one of the most international ministries in the world.

I sometimes wonder if the Middle East will ever know peace. The number of times this region has had to rebuild and lift itself up again is really mind-blowing and frankly quite depressing. In the 64 years I’ve been alive, I’ve seen Lebanon “die” and “rise” again about five times. Set aside the physical destruction, the Middle East constantly finds itself in an ethnic and denominational power struggle: who will rule whom? Who will have the last say? If only all this pain and destruction was worth it. Take the Israel-Palestine conflict. It really seems unresolvable, no matter how many people suffer and die.

All this seemed too unfair to the young adolescent I was, growing up in warzone Beirut. Up until recently, I used to be stripped in every airport and interrogated, just because I had a Lebanese passport. The prospect of that peace seemed to be getting further away.

I moved to Cyprus in 2005 and subsequently received my Cypriot citizenship. Getting a European passport, though, didn’t seem to alleviate the pain and struggle which comes with being Armenian and Lebanese. I have been working in the Arabian (Persian) Gulf countries for the last 31 years. I often find myself asking the recurring question: “Where is home”? Is it Beirut, Nicosia, or better yet, Kuwait? I suppose I am what you may call the archetype of an Armenian living in diaspora.

Regardless, I found myself having three different identities and “homes”. I suppose two homes, as I’ve never really lived in Armenia… or been able to.

In 1915, my father was deported from his home in Aintab. He was barely a year old then. His family settled in Aleppo, Syria, and then moved to Beirut, Lebanon, where I was born. My family lost 25 of its members during the Armenian Genocide perpetrated by Ottoman Turkey from 1908 to 1915, along with all their physical properties. I haven’t met them, but I know them because I cherish the memories and legacies they left behind through those who survived. I see their faces every time I look through old pictures in my family album and imagine a life in Aintab, and what it would have been like if they had lived.

I’m a third-generation Armenian living in diaspora because my ancestors were forced to flee in 1915 during the Armenian Genocide. Although my generation didn’t directly witness the Genocide, we carry the pain of it. We carry the pain of our ancestors who were massacred and the pain of being deprived of living on our land that is rightfully ours.

In the years since the Genocide, Armenians have learned to live and prosper in a diaspora, away from home, but never, not even for a minute, giving up on that hope that we will one day go back home. Albeit home (historical Armenia) is not “reachable” at the moment, the republics of Armenia and Artsakh are.

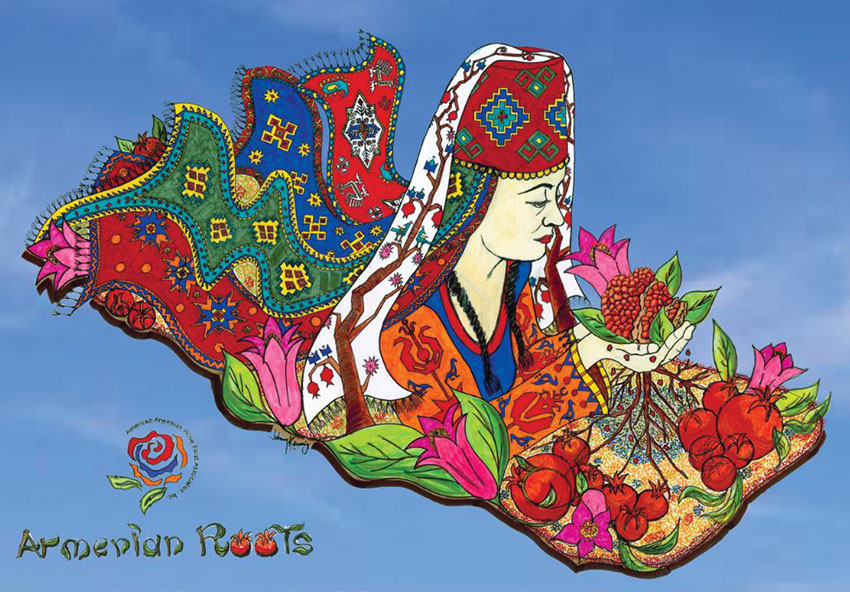

I was fortunate enough to visit Armenia and Artsakh several times. On my last visit in September 2019, I was in Stepanakert, Artsakh, presenting my book Armenian Diasporan Lives: As I Saw Them at the National University of Artsakh. I also had the privilege of meeting the Minister of Foreign Affairs with whom I shared my love for the land. I enjoyed the beautiful country and my fellow Armenians living in Artsakh. Armenians have an incredible passion for their land and for the Armenian identity. The landscape is so beautiful and the people even more so. One year on, and I am still in awe of its beauty. It is truly life changing. For some context on Artsakh and the war that took place, here’s a little history of the region:

The Republic of Artsakh or Nagorno Karapagh is a de facto independent state and shares borders with Armenia, Iran, and Azerbaijan. Artsakh is considered to be the second Armenian Republic. The capital of Artsakh is Stepanakert and is the largest city of the Artsakh Republic. It is the cultural, educational, and economic center of the region. Stepanakert is located on the eastern slopes of Karapagh’s mountain chain, at the left bank of the Vararakn River. The capital was originally named after this river but was later renamed in honor of Bolshevik politician and revolutionary Stephan Shahumian.

Stepanakert is a modern city with wide, clean streets, new builds, and nice parks. The predominantly Armenian-populated region (99.7%) of Nagorno-Karapagh was claimed by both the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic and the First Republic of Armenia when both countries became independent in 1918 after the fall of the Russian Empire, and a brief war over the region broke out in 1920. The dispute was largely shelved after the Soviet Union established control over the area and created the Nagorno-Karapagh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) within the Azerbaijan SSR in 1923.

When the Soviet Union fell, the region re-emerged and became the subject of what I see is a series of endless wars and suffering between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In 1991, a referendum was held in the NKAO and the neighboring Shahumian region which resulted in a declaration of independence. Ethnic conflict between Armenians and Azeris led to the 1991–1994 Nagorno-Karapagh War, which ended with a ceasefire along the current borders.

The 44-day war on Artsakh, by Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Islamist jihadists, was much more than a matter of life or death for Armenians. It was a matter of fighting for the 1.5 million Armenians who were killed during the 1915 Genocide. The war ended with Armenia’s defeat and over 5000 young soldiers killed. We also lost quite a bit of land, which included historical churches and monasteries. Azerbaijan and Turkey consist of more than 90 million people, whereas Armenia and Artsakh are barely three million put together. I cannot help but be reminded of the story of David and Goliath in the Bible, mainly when looking at the power discrepancies which I will touch on more towards the end of my piece.

Is history repeating itself? Most likely, yes. 106 years on, we are faced with the same power trying to bring us down to our knees. The pain just seems to be never-ending.

When reflecting on the idea of how pain and suffering can bring people together, I stumbled on Walter Brueggemann’s work. Brueggemann believes that bringing people to engage with their experiences of suffering and death energizes and links people to hope. This hope then helps the individual to cut through the despair, which might otherwise seem unresolvable or unending.

The human and physical destruction of the recent war has been a major setback for Armenians, but it can still generate this same hope.

According to Bruegemann, newness in one’s life is given by God and is supposed to be the only real source of energy. He explains his assertion by linking Exodus with what Jesus did on the cross. For Bruegemann, Jesus’ death-resurrection was the absolute Exodus, showing that ultimately hope is always given to us and not necessarily generated by us. This is how I choose to describe my journey.

Maybe wars and destructions have in very rare occasions served as forces for good. But violence generates more violence. What is most needed today, as Apostle Paul says, is “fighting the good fight”.

The good fight does not need Su-2 or drones. The good fight is a life changing process, which is initiated by the acceptance, understanding, and respect of the Other, which I’ve come to realize in my last 41 years in the Gulf is a vital component for peace, regardless of the latter’s background.

Today, as I look at a shattered Artsakh, I know that no war or physical force can eradicate its beauty, but that’s from a patriot’s perspective. From an Armenian’s perspective living in a scattered diaspora, I see bloodshed and unrest: a very high price we continue to pay, in our struggle for peace and justice. As a Lebanese and Middle Eastern, I am much too familiar with that feeling.

Perhaps if these wars were the right kind of wars, assuming there is such a thing, the world could become a better place.

I don’t think my pain and struggle will ever go away, and I have somehow come to terms with the fact that I may never, in my lifetime, see peace or fair retribution. One thing I know, though, is that I will carry on fighting the fight for the Good, regardless of whether I make it to the finish line or not.

Reverting to the biblical story of David and Goliath, David beats Goliath even though the fight and power dynamics were uneven. David beats Goliath because he was fighting for the GOOD cause.

Fighting the good fight is not easy, but it is worth it. That’s the only way I see forward.

The GOOD will eventually win.

* Dr Hrayr Jebejian is General Secretary of the Bible Society in the Arabian-Persian Gulf . He holds a Bachelors degree in Business Administration from Haigazian University, Master of Science degree in Agricultural Economics from American University of Beirut and Doctor of Ministry degree in Bible Engagement from the New York Theological Seminary. He has traveled extensively all around the world and has delivered lectures, interviews on Christian presence in the Middle East, Biblical and inter-church relations and on socio-cultural and ethnic issues. Jebejian is the author of three books, along with articles published in academic journals and encyclopedias. He is a recipient of the Ambassador of the Motherland medal from the Ministry of Diaspora of the Republic of Armenia.

Email: [email protected]