“Stand tall! Think tall! Feel tall! You are tall!”

The command of Mr. Kahn, P.E. coach at Paul Revere Junior High School, was echoing in his mind, but by this early morning of April 23, 2001, Raffi K. Hovannisian was far, very far, from the shady groves of Brentwood, California.

In the mirror of his bedroom—on the third floor of a house overlooking a strange, circular city—Raffi stood before himself. He combed his hair and moustache; they were graying. He tightened his tie.

Behind Raffi, on the bed, his wife and children were asleep. They could not imagine what he was about to do. Very quietly Raffi opened the top drawer of the dresser. He found what he was looking for. It was a blue passport.

He picked it up and pushed it into his breast pocket.

An old Zhiguli, a square Soviet car, was waiting for Raffi outside. He got into the passenger’s seat and spoke a few Armenian words to the driver. The car grumbled in the still morning and began its descent to Yerevan, the pink and gold capital of the independent Republic of Armenia.

And soon Raffi saw them, the great white mountains—the lesser and greater peaks of Mount Ararat—glowing vast and eternal just beyond the city, as if they had been freshly painted upon a bleak canvas. Those awesome mountains, where Noah’s Ark is said to have landed, had once served as the symbol of a unified homeland. But today, rising through fog and blizzard, Ararat stood as the behemoth boundary between two homelands: a problematic post-Soviet state to the east and the memory of a murdered civilization to the west—reality and dream.

Ararat itself was part of the dream.

It stood in Turkey, on the western side of the border.

It was an odd story about our family—a story few people actually understood, or believed. After the genocide of 1915, when the Young Turk regime annihilated the Armenian people, my great-grandfather escaped from Western Armenia and sought refuge in the San Joaquin Valley of California. He built a new home there, cultivated a farm. My grandfather, too, accepted his fate in the diaspora. My father, it was assumed, would accept his.

But in 1989 the unimaginable happened.

Inspired by a democratic movement in Eastern, then Soviet, Armenia, my father decided to leave the United States. He left his law firm and friends and extended family, and he told his children that they were going home. My father called it “return.” My mother called it “vacation.” She had no idea that twelve years later, she would still be on vacation.

The Zhiguli stopped twice in the city—first to pick up Zori Balayan, a prominent journalist, and then Archbishop Mesrob Ashjian; two witnesses would be required for the morning procedure—and made its way to 18 Baghramyan Boulevard, a small gray building with a round window opening toward a bustling street. This was the most famous window of the entire republic.

Vice Consul Gregory Morrison greeted Raffi and his two witnesses outside. “You see these people?” he said, looking down the long line of Armenians.

“These are your people. All of them want to come to the United States.”

Raffi said nothing. He only smiled and followed the American inside. In a picture frame hanging on the wall, George W. Bush had recently replaced Bill Clinton.

Raffi was quiet through much of the briefing and the paperwork, though he did emerge from his silence to inquire if anybody had done this before him. The answer was no.

“You understand that once you give up your citizenship, you can never reclaim it?” Vice Consul Morrison asked, sliding the document toward Raffi. The vice consul, the journalist, the archbishop—they were all moved by the tragic beauty of this ceremony.

“Yes,” Raffi said.

Raffi read the conditions of renunciation: “I hereby absolutely and entirely, without mental reservation, coercion or duress, renounce my United States nationality together with all rights and privileges and all duties of allegiance and fidelity thereunto pertaining.”

The embassy of the United States in Yerevan was silent when Raffi took his blue pen to the line beneath the print.

He wrote his initials in clean Armenian cursive, but his hand did not stop where it was supposed to. In his decisive last gesture as a United States citizen, Raffi returned the pen to the beginning of the signature and encircled what he had just written: RKH.

The irreversible act was done, and now the vice consul asked if, for the record, Raffi wished to attach a written explanation. He did—just one sentence: I am compelled to do so for the sole purpose of advancing the standards of liberty, democracy, and rule of law in the Republic of Armenia and in the absence there of a legal provision for dual citizenship.

Excerpt from Garin Hovannisian’s “Family of Shadows”

The following excerpt is adapted from Garin K. Hovannisian’s memoir, Family of Shadows: A Century of Murder, Memory, and the Armenian American Dream, which HarperCollins will release on September 21. For more information, visit: www.familyofshadows.com

- No comments

- 4 minute read

The Positive Outcomes of the Brussels Meeting

By: K. KHODANIAN Last September, Azerbaijani troops invaded Artsakh, prompting over…

- MassisPost

- April 14, 2024

- No comments

- 2 minute read

It’s Not Armenia That Has Distanced Itself From Russia, but Rather the Other Way Around

By K. KHODANIAN Armenia and Russia are experiencing notable tensions in their…

- MassisPost

- April 7, 2024

- No comments

- 2 minute read

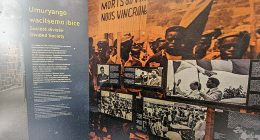

Stating the Obvious: Kigali Genocide Memorial and the Armenian Genocide

Gomidas Institute Initiates Campaign on Kigali Genocide Memorial and the Armenian…

- MassisPost

- April 7, 2024

- No comments

- 3 minute read

How an Armenian Family Helped in Building Modern Egypt

By ARUNANSH B. GOSWAMI Recently the author of this article was in…

- MassisPost

- April 5, 2024

- No comments

- 5 minute read